University of Warsaw

Faculty of Philosophy

Department of Ethics

Center for Bioethics and Biolaw

email: j.rozynska@uw.edu.pl

Biomedical research involving minors or other persons incapable of giving consent raise many complex ethical issues, particularly when the research offers no prospect of direct therapeutic benefit to the participants. To protect such individuals from exploitation and undue risks that compromise their dignity, integrity, rights, and well-being, most ethical and regulatory standards prohibit the enrollment of incompetent subjects in studies that have no therapeutic potential, unless participation involves only minimal risk and burden. This well-established standard has also been adopted by Regulation (EU) No 536/2014 on Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products for Human Use, and Repealing Directive 2001/20/EC, which recently entered into force. However, the provisions of the Regulation defining the minimal risk threshold are so ambiguous and confusing that they can easily be interpreted in ways that are unethical and inconsistent with the overall goals of the legislation. This paper critically analyzes the minimal risk requirement of the Clinical Trials Regulation and offers an ethically and legally sound interpretation of the threshold in “non-therapeutic” clinical trials involving selected categories of vulnerable subjects.

Keywords: research ethics, clinical trials, minimal risk, EU Regulation on Clinical Trials

Regulation (EU) No 536/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products for Human Use, and Repealing Directive 2001/20/EC,1 further referred to as the CTR, entered into force on 31 January 2022,2 after more than six years of development of the Clinical Trials Information System. The System consists of a centralized web portal and a clinical trials database, two key tools for harmonizing the rules for submitting, evaluating, approving, monitoring, reporting and conducting clinical trials across the EU and for increasing the transparency of information on clinical trials in the region. The CTR brings significant changes to the regulatory framework and practice of clinical trials in the EU and, indirectly, to the global clinical trial regulatory landscape.3 Some of them are long-awaited and more than welcome, while others still raise numerous questions.4 This paper deals with a small (in terms of text length), but very important novelty, namely the adoption of a minimal risk threshold by the CTR, i.e., the requirement that was completely missing in the repealed Clinical Trials Directive 2001/20/EC.5

The term “minimal risk” appears in five provisions of the CTR:

All these provisions contain the phrase “minimal risk” without providing its definition or explanation. Moreover – as shown in Table 1 below – they use the phrase in different sentence structures and in reference to different categories of trials and research risks, thus suggesting the presence of four distinct concept (standards) of minimal risk under the CTR. I will refer to them as: “additional minimal net risk,” “comparative minimal net risk,” “minimal net risk simpliciter,” and “comparative minimal risk.”

Table 1. Four concepts of minimal risk under the CTR

| Additional minimal net risk | |

Article 2.2(3)(c) (defining „low-intervention clinical trial”) |

“the additional diagnostic or monitoring procedures [involved in such trial – Author] do not pose more than minimal additional risk or burden to the safety of the subjects compared to normal clinical practice in any Member State concerned” |

| Comparative minimal net risk | |

Article 31.1(g)(ii) (regarding “non-therapeutic” clinical trials on incapacitated participants) |

“trial will pose only minimal risk to, and will impose minimal burden on, the incapacitated subject concerned in comparison with the standard treatment of the incapacitated subject’s condition” |

Article 32.1(g)(ii) (regarding “non-therapeutic” clinical trials on minors) |

“a clinical trial will pose only minimal risk to, and will impose minimal burden on, the minor concerned in comparison with the standard treatment of the minor’s condition” |

| Minimal net risk simpliciter | |

Article 33(b)(iii) (regarding “non-therapeutic” clinical trials on pregnant or breastfeeding women) |

“the clinical trial poses a minimal risk to, and imposes a minimal burden on, the pregnant or breastfeeding woman concerned, her embryo, foetus or child after birth” |

| Comparative minimal risk | |

Article 35.1(f) (regarding emergency trials with potential of direct benefit to participants) |

„the clinical trial poses a minimal risk to, and imposes a minimal burden on, the subject in comparison with the standard treatment of the subject’s condition” |

The suggested variety of minimal risk standards under the CTR regulatory framework contrasts with the generally accepted premise that the legislator is a rational actor who follows (among other things) the principle of consistency.9 This principle requires the precise and consistent use of terms in legislation and is reflected in one of the most fundamental rules of legal interpretation, also known as the “presumption of consistent usage.”10 The latter states that identical terms used in different parts of the same legal text should be interpreted as having the same meaning; conversely, differences in words indicate a difference in meaning. Thus, it suggests that the phrase “minimal risk” should be given a consistent meaning in all relevant CTR provisions.

However, the search for a proper understanding of the EU minimal risk threshold cannot begin and end with linguistic and/or systematic interpretations of the CTR provisions, as they may not be able to remove ambiguities or may even lead to conclusions that are unacceptable in the light of the axiological background and intention of the given legislation. Particular attention must always be paid to the general aim and purpose of the CTR (teleological interpretation),11 which is to ensure that in all clinical trials conducted in the EU the rights, including the right to physical and mental integrity, safety, dignity and well-being of trial subjects are protected and prevail over all other interests, and that the data generated are reliable and robust (cf. Recital 1, Articles 3 and 28.1(d) of the CTR). It has already been noted in the literature that the CTR provisions on minimal risk in “non-therapeutic” clinical trials involving vulnerable subjects are so poorly and ambiguously drafted that they are open to unacceptable interpretation, leaving subjects without adequate protection.12

The aim of this paper is to clarify this conceptual and normative confusion by providing an ethically and legally sound interpretation of the minimal risk standard under the CTR. The following analysis will focus on the most controversial minimal risk threshold, i.e., the comparative minimal net risk in “non-therapeutic” trials involving minors and incapacitated adults. However, other provisions of the CTR that incorporate the concept of minimal net risk will be discussed to the extent that they provide important insight into an appropriate interpretation of the CTR minimal risk threshold in such “non-therapeutic” studies.

2. Preliminary remarks on the minimal risk standard in the international and European regulatory framework for “non-therapeutic” biomedical research

“Non-therapeutic” research is an important but controversial vehicle for progress in biomedical science and clinical practice. By definition, such studies put participants at risk solely for the benefit of science and society, with no compensating potential for direct therapeutic benefit. When competent individuals are involved in “non-therapeutic” research, their exposure to net risk is justified, at least in part, by their autonomous decision to enroll in such studies, i.e., their consent. But when a “non-therapeutic” study involves subjects who are unable to give fully informed and/or voluntary consent – such as children or incompetent adults – there is still no consensus about what (if anything) justifies exposing them to potential harm for the benefit of others.13

Many early ethical standards for biomedical research involving humans (e.g., the Nuremberg Code,14 the Declaration of Helsinki 1964-199615) protected incompetent individuals from research net risk, by excluding them from participation in “non-therapeutic” studies. This approach was vigorously defended by Paul Ramsey in his famous polemic with Richard McCormick on the ethics of pediatric research without a therapeutic potential.16 McCormick argued that parental consent can justify the child’s enrollment into a valuable “non-therapeutic” study that poses only “no discernible risk” because such consent is based on what the child ought to wish for herself and others as a social being bound by duties of social justice.17 Ramsey responded that McCormick relies on unwarranted assumption about the existence of duty to participate in research, and that parents lack the moral authority to provide consent for interventions that are not in the best interest of their children, including those related to research.18 He asserted that “to experiment on children in ways that are not related to them as patients is already a sanitized form of barbarism; it already removes them from view and pays no attention to the faithfulness-claims which a child, simply by being a normal or a sick or a dying child, places upon us and medical care.”19

The initial “protection-by-exclusion” approach focused on the interests of individual research subjects, but remained entirely blind to the broader clinical, social, and ethical “costs” of banning “non-therapeutic” research on minors, incompetent adults and representatives of other vulnerable groups. It contributed significantly to a reduction in research on therapies specifically designed for these populations and targeted to their specific clinical needs. As a result, these populations have become “therapeutic orphans” without access to proven, safe and effective treatments.20

By the end of the 20th century, the negative consequences of the “protection-by-exclusion” approach had become widely recognized, and the approach was rejected by the majority of research ethicists and policy makers as too restrictive and incompatible with the requirements of justice and the principles of beneficence and non-maleficence.21 It has gradually been replaced by an ethical and regulatory consensus that “non-therapeutic” studies involving incompetent participants may (or even should) be conducted,22 provided that special measures are taken to protect subjects from undue risk and exploitation, including the requirement of minimal risk23 (and burden24).

At the beginning of the 21st century, the minimal risk threshold for “non-therapeutic” research involving participants who are incapable of giving consent has been endorsed by most international ethical and/or legal standards for biomedical research involving human subjects. Most notably by the WMA Declaration of Helsinki25 (par. 28), UNESCO Universal Declaration of Bioethics and Human Rights26 (Article 7), the CIOMS International Ethical Guidelines for Health-related Research Involving Humans27 (Guideline 4), the Council of Europe’s Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine: Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine,28 and the Additional Protocol to the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, concerning Biomedical Research29 (Articles 15 and 17). It is worth noting, however, that the ICH Guideline for Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP)30 – a global ethical and scientific quality standard for the design, conduct, recording, and reporting of clinical trials, adopted in 1996 by representatives of authorities and pharmaceutical companies from the EU, Japan, and the United States – did not use the term “minimal risk,” but instead required that the risk of “non-therapeutic” trials involving subjects who cannot give consent be “low” (Article 4.8.14(b)), and „the negative impact on the subject’s well-being is minimized and low” (Article 4.8.14(b)(c)).31 The repealed EU Clinical Trials Directive followed ICH-GCP risk mitigation requirements, but only selectively with respect to risk minimization, and thus remained one of the few exceptions to the growing regulatory consensus on the minimal risk threshold for “non-therapeutic” trials. The Directive stipulated that “non-therapeutic” trials with vulnerable subjects must always be designed „to minimise pain, discomfort, fear and any other foreseeable risk in relation to the disease and developmental stage; both the risk threshold and the degree of distress have to be specially defined and constantly monitored” (Article 4(g); Article 5(f)). In other words, the Directive required that the risk associated with “non-therapeutic” clinical trials on persons incapable of giving consent be minimized, but not below a certain minimal threshold.

It must be emphasized that the Clinical Trials Directive only established minimum requirements for the protection of trial subjects. Thus, Member States were free to adopt stricter rules than those laid down in the Directive, as long as they were “consistent with the procedures and time-scales specified therein” (Article 3.1). And some national legislators have done so.32 As a result, the Directive did not harmonize the legal protection of clinical trial participants, especially those unable to give consent such as children and incapacitated adults. The regulatory diversity in this area has been exacerbated by two factors: (i) the ambiguity of the Directive’s provisions, which led to (early) discussions on the very permissibility of involving persons incapable of giving consent in “non-therapeutic” trials under EU law;33 and (ii) the normative tension between the Directive’s “risk minimization” requirement and the much stricter minimal risk threshold endorsed by other prominent regulations, notably by the Council of Europe’s Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine and the Additional Protocol to the Convention concerning Biomedical Research.34

To ensure an adequate protection for minors participating in clinical trials while promoting high quality pediatrics studies, and to facilitate harmonized application of the Directive across the EU, in February 2008 the European Commission released “Ethical Considerations for Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products Conducted with the Paediatric Population. Recommendations of the Ad hoc Group for the Development of Implementing Guidelines for Directive 2001/20/EC Relating to Good Clinical Practice in the Conduct of Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products For Human Use”35 (further referred to as the 2008 Recommendations). The document integrated ethical principles and requirements for clinical trials involving children contained in various European, U.S. and international ethical and legal sources. Although it had no legally binding force, it soon became an important reference for researchers and research ethics committees (RECs) in all EU countries. Unfortunately, it offered little assistance in clarifying criteria for acceptable level of risk in “non-therapeutic” pediatric clinical trials. Mainly because the authors of the 2008 Recommendations made a controversial decision to follow the U.S. federal regulations on permissible risk in pediatric studies.36

After the US regulation, the 2008 Recommendations distinguished three levels of acceptable risk in research on minors, namely: “minimal risk,” “minor increase over minimal risk,” and “greater than minor increase over minimal risk.”37 They further suggested that minimal risk should be defined as “probability of harm or discomfort not greater than that ordinarily encountered in daily life or during the performance of routine physical or psychological examinations or tests.”38 Such a comparative way of defining minimal risk has been adopted not only by the U.S. regulators, but also by some other legislators and policy makers.39 However, by not providing any additional comments on this definition, the Ad Hoc Group for the Development of Implementing Guidelines for Directive 2001/20/EC has shown itself to be completely ignorant of the decades of critical debate on the justification and appropriate interpretation of the definition. Most importantly, the group did not say which of the two comparative standards covered by the definition, i.e., the daily life standard or the routine examination standard, should be used as the benchmark for minimal risk in “non-therapeutic” pediatric trials , and whose risks of daily life or of routine examination should constitute the benchmark. Both of these issues have been extensively discussed in the literature and policy documents for almost thirty years.40

Loretta Kopelman famously argued that each of the standards is ambiguous because it can be interpreted in a relative way, as referring to the daily life/routine examination risks of the particular group of research subjects, or in an absolute way, as referring to the daily life/routine examination risks of a normal, average, healthy person.41 She noted that relative interpretation raises serious problems because different populations face different risks in their daily lives or are exposed to different risks in their routine examinations. For example, compare the risks faced by children living in a dangerous or heavily polluted environment with the risks faced by children living in a safe and healthy environment; or compare the risks associated with routine treatment of minor patients suffering from an oncological disease with the risks associated with diagnostic procedures routinely performed on healthy children. Thus, the relative interpretation allows the exploitation of children who are already exposed to greater risks because of their medical or socio-economic conditions, and may lead to an unfair and inequitable distribution of research risks. It should therefore be abandoned.

Following Kopelman,42 the majority of American research ethicists, advisory bodies, and regulators have opted for the absolute interpretation of the minimal risk threshold (also referred to as the “uniform standard”), with increasing emphasis on the daily risk standard as less stringent and more research-friendly than the routine examination standard for healthy children. These include the most prominent U.S. advisory committees, such as the National Human Research Protections Advisory Committee (NHRPAC),43 the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies,44 and the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections (SACHRP)45 providing expert advice and recommendations to the Secretary of Department of Health and Human Services. It also includes the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.46 All these bodies agree that the standard of minimal risk should be interpreted “as those risks encountered during daily life by normal, average, healthy children living in safe environments or during the performance of routine physical or psychological examinations or tests”47 and indexed to the experiences of children of the same age and developmental stage as the subject population.48

The EU 2008 Recommendations remained silent on all these problems with the daily risk standard and the routine examination standard. Moreover, by adopting a controversial category of “minor increase over minimal risk”49 and by allowing for a minor increase over minimal risk in “non-therapeutic” trials with “benefit to the group, and with the benefit to risk balance being at least as favourable as that of available alternative approaches,”50 they further exacerbated the regulatory discrepancies between the EU guidelines and the Council of Europe’s standards for the protection of vulnerable research subjects.51 In contrast to the 2008 Recommendations, the Explanatory Report to the Additional Protocol to the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine concerning Biomedical Research explicitly stressed that “the risk for such [incompetent] participants cannot be increased beyond minimal even if the research promises a higher level of benefit.”52

I will return to some of the above problems in the following parts of the paper because, unfortunately, many of them have not been resolved by the new Recommendations on „Ethical Considerations for Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products Conducted with Minors,” issued in 2017 by the Expert Group on Clinical Trials for the Implementation of Regulation (EU) No 536/2014 on Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products for Human Use53 (hereafter referred to as the 2017 Recommendations). The document replaces the 2008 Recommendations that applied to the repealed Clinical Trials Directive.

3. “Comparative minimal net risk” threshold

As noted above, the CTR introduces a threshold of the permissible level of net risk in “non-therapeutic” clinical trials involving minors (Article 32.1(g)(ii)) and incapacitated adults (Article 31.1(g)(ii)). The new requirement stipulates that the risks associated with such studies should be minimal “in comparison with the standard treatment” of the subject’s “condition.” This comparative approach to defining the threshold has already been criticized in the literature.54 However, the critics have failed to acknowledge that the CTR also endorses other concepts of minimal net risk that may shed light on the appropriate interpretation of the threshold, and that some of these other concepts have already been discussed by the Expert Group on Clinical Trials for the Implementation of Regulation No 536/2014.

Evidently, the CTR comparative minimal net risk threshold suffers from serious interpretative problems. Taken literally, it requires a comparison of trial risk with standard treatment, which are two completely different and incomparable concepts. “Risk” stands for the probability of harm occurring as a result of participation in a clinical trial, whereas the term “standard treatment” refers to a medical treatment that is the standard of care for individuals with a particular disease or condition. By definition, “non-therapeutic” clinical trials involve only net risk. Moreover, the net risk of the trial (as well as its potential scientific benefit) is often uncertain and difficult or impossible to specify and quantify. In contrast, standard treatment involves therapeutic benefits and potential harms because “no drug is without risk and all medicines have side-effects, some of which can be fatal.”55 Both the benefits and the risks of a given standard treatment are already known to the extent that medical experts and competent regulatory authorities consider the former to outweigh the latter. In other words, there is no net risk associated with the standard treatment.

Thus, comparing the net risk of the trial to the standard treatment is like comparing apples and oranges. Rather, it seems reasonable to assume that the risks of the “non-therapeutic” clinical trial should be judged against the risks of the standard treatment. Unfortunately, this clarification does not resolve all of the interpretation problems associated with the phrase “in comparison to the standard treatment.” The wording of the phrase suggests that what counts as a permissible level of net risk involved in “non-therapeutic” studies on minors or incapacitated adults (i.e., minimal risk) is somehow related to or dependent on the level of risk associated with the standard treatment for the trial subjects’ condition. But it does not explain or justify this relationship. And there seem to be at least three ways to understand the sentence.

3.1. Three interpretations of the “comparative minimal net risk” threshold

The first interpretation follows the above-mentioned 2017 Recommendations on “Ethical Considerations for Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products Conducted with Minors.” Similar to the 2008 Recommendations, the 2017 document states that under the CTR, risks of “non-therapeutic” studies in children are considered minimal if the likelihood and magnitude of these risks are “similar to risks ordinarily encountered in a child’s daily life, or during routine physical or psychological examinations (…) This means that the levels of risks and burden for participants should be assessed relative to, and be reasonably commensurate with the standard treatment they receive.”56 The Expert Group further explains that there is no universal and pre-established threshold of permissible risk in “non-therapeutic” clinical trials with children. Rather, the level of risk that is considered minimal and acceptable varies in relation to the risks associated with the standard treatment for the participants, their disease, health status, and prior experience.57

The postulated „reasonable commensurability” between the research risk and the risk of the standard treatment supports the following interpretation of the CTR threshold of comparative minimal net risk: A “non-therapeutic” clinical trial involves only minimal risk if the level of risk of the trial is commensurate with (similar to) the level of risk associated with the standard treatment of the subject’s condition.

The second interpretation of the phrase „pose only minimal risk in comparison with the standard treatment” emphasizes the difference between the level of risk associated with the “non-therapeutic” clinical trial and the level of risk associated with the standard treatment. As in commonly used sentences such as: “The cost of building a swimming pool is minimal in comparison to the cost of building a villa” or “The tooth-pain is minimal in comparison to the pain of childbirth,” the phrase “minimal risk in comparison with the standard treatment” can be interpreted to require that the clinical trial be considerably less risky than the standard care. Thus, under this reading: A “non-therapeutic” clinical trial involves only minimal risk if the level of risk of the trial is significantly lower than the level of risk associated with the standard treatment of the subject’s condition.

The third interpretation is the opposite of the second one and argues that the contested phrase indicates an upper limit of acceptable risk associated with participation in “non-therapeutic” clinical trials that exceeds the level of risk associated with standard treatment. Likewise in a comparative sentence: “The increase of maintenance costs of the building after renovation are minimal in comparison to its maintenance costs before the renovation.” Thus, this interpretation suggests the following reading of the threshold: A “non-therapeutic” clinical trial involves only minimal risk if the level of risk of the trial is no more than minimally higher than the level of risk associated with the standard treatment of the subject’s condition.

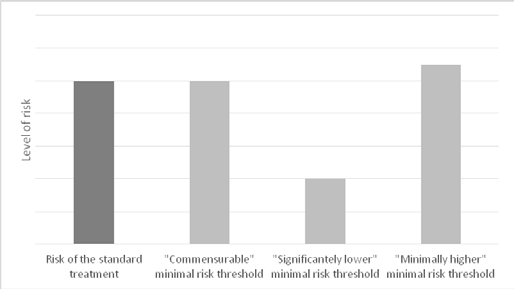

As Figure 1 shows, the above interpretations of the CTR threshold of comparative minimal net risk set risk limits at different levels. However, all of these interpretations ultimately determine what constitutes minimal net risk relative to the level of risk associated with standard treatment. Consequently, they all suffer from three serious and irreparable conceptual and normative problems that make them ethically unacceptable. These problems are referred to as: (i) indeterminacy objection, (ii) exploitation objection, and (iii) ethical disanalogy objection.

3.2. Critique of the “comparative minimal net risk” threshold

The indeterminacy objection points to the ambiguity and vagueness of the terms “standard treatment” for the “subject’s condition” used in the analyzed provisions of the CTR.58 The CTR defines “normal clinical practice” as “the treatment regime typically followed to treat, prevent, or diagnose a disease or a disorder” (Article 2.2(6)). However, the relationship between “normal clinical practice” and “standard treatment” remains unexplained. Furthermore, it is unclear what the terms “standard treatment” for the “subject’s condition” signify in the following scenarios: (i) when there is no standard treatment for the subjects’ clinical condition; (ii) when two or more treatment strategies involving different levels of risk are used in clinical practice and all are considered standard care for the participants’ condition; (iii) when the study is multisite project and different standards of care for the participants’ condition are employed in different sites59 (e.g., high income country v. low income country); (iv) when the trial involves subjects suffering from different background conditions, thereby eligible for different treatment regimens involving different levels of risks (and burdens); or (v) when the trial involves individuals who suffer from an illness that is not directly targeted by the study, and – consequently – the risks associated with their standard therapeutic procedures are entirely unrelated to the risks of the proposed study; or (vi) when the study population comprises only healthy individuals, i.e., persons in a “healthy condition.”

The Expert Group on Clinical Trials for the Implementation of the CTR does not explain or even address these issues. In fact, their 2017 Recommendations contribute to the confusion by referencing uncritically the U.S. federal definition of minimal risk and by explicitly endorsing a relative interpretation of the routine examination (standard treatment) standard.60

The exploitation objection is closely related to the previous concern and it targets the ethically unacceptable consequences of the CTR’s adoption of the relative interpretation of the comparative threshold of minimal net risk. The 2017 Recommendations assert that “there is no set definition that will apply to all clinical trials with minors; therefore, ‘minimal risk and burden’ will have to be viewed in the context of the disease, health status, prior experiences and standard treatment of the participants.”61 Thus, they accept the controversial logic that the riskier the standard treatment for the population being studied, the higher the level of risk in “non-therapeutic” clinical trials with that population can be considered minimal.

As already mentioned, this line of reasoning has been rejected by prominent research ethicists, experts bodies and policy makers.62 The ethical consensus on this issue has been reaffirmed by the most recent 2016 version of the International Ethical Guidelines for Health-Related Research Involving Humans, developed by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences in collaboration with the World Health Organization. The Guidelines recall that the main difficulty with any relative interpretation is that “different populations can experience dramatic differences in the risks of daily life or in routine clinical examinations and testing. Such differences in background risk can stem from inequalities in health, wealth, social status, or social determinants of health. Therefore, research ethics committees must be careful not to make such comparisons in ways that permit participants or groups of participants from being exposed to greater risks in research merely because they are poor, members of disadvantaged groups or because their environment exposes them to greater risks in their daily lives (for example, poor road safety). Research ethics committees must be similarly vigilant about not permitting greater research risks in populations of patients who routinely undergo risky treatments or diagnostic procedures (for example, cancer patients). Rather, risks in research must be compared to risks that an average, normal, healthy individual experiences in daily life or during routine examinations.”63

Finally, the ethical disanalogy objection points to a fundamental lack of ethical justification for assuming that the level of risk associated with the standard treatment should be used as a reference point for delineating an acceptable level of risk in research that offers no potential for clinical benefit. The risks associated with the standard treatment are considered acceptable because they are justified („compensated”) by the expected therapeutic benefits to the patient. This justification does not apply to the risks of “non-therapeutic” trials, because – by definition – these risks are not compensated by expected direct clinical benefits to the participants. The net risks are incurred solely for the benefit of science and society. Therefore, in order to be acceptable, they must be justified by the potential social and scientific value of the study. Nothing else. The ethical disanalogy objection provides the strongest argument for rejecting any comparative definition of minimal net risk referring to the risk of standard treatment or routine examination.64

4. Non-comparative minimal risk thresholds

I have argued so far that the CTR minimal risk threshold in “non-therapeutic” clinical trials involving minors or incapacitated adults, when interpreted in comparative (and relative) terms, is prone to serious conceptual and normative problems. In what follows, I will explore whether two non-comparative concepts of minimal net risk present in the CTR may be helpful in developing an ethically sound minimal risk standard in “non-therapeutic” trials on vulnerable populations.

4.1. The “minimal net risk simpliciter” threshold

A promising alternative concept of minimal net risk appears in the CTR provisions for clinical trials involving pregnant and breastfeeding women. The CTR stresses that these groups of women require specific protection (recital 27), especially when participating in “non-therapeutic” trials (recital 34). Article 33(b)(iii) further states that a clinical trial which has no direct benefit for the pregnant or breastfeeding woman concerned, or her embryo, foetus or child after birth, can be conducted if it „poses a minimal risk to, and imposes a minimal burden on, the pregnant or breastfeeding woman concerned, her embryo, foetus or child after birth.” Unfortunately, neither the CTR nor the Expert Group on Clinical Trials for the Implementation of the CTR provide specific criteria for defining this threshold. Therefore, it can be argued that the evaluation of the risks (and burdens) associated with such trials should be left entirely to the judgment of the research ethics committee (REC).

This approach to assessing whether a clinical trial meets the requirement of minimal risk (and burden) – often referred to as a purely procedural approach – has significant advantages in that it is deliberative, project- and context-sensitive, and flexible, but it is not without serious shortcomings.65 Empirical studies66 suggest that the lack of guidelines for risk assessment may lead to unwarranted diversity and arbitrariness of risk judgments by RECs, and consequently to unequal and inadequate protection of the safety and rights of “non-therapeutic” clinical trial participants.67 These consequences are ethically and practically worrisome, especially when vulnerable populations are the subjects of research studies. Therefore, the purely procedural approach should be abandoned. The RECs need guidance on how to assess the risk associated with “non-therapeutic” studies, most preferably in the form of a clear, ethically sound and practically useful definition of the threshold,68 coupled with the list of exemplary minimal risk research procedures to establish “palpable and familiar benchmarks.”69

4.2. The “additional minimal net risk” threshold

The next non-comparative concept of minimal net risk is contained in the CTR’s definition of a newly introduced category of “low interventional clinical trials,” which – due to their nature – are subject to a less stringent and consequently less burdensome and costly regulatory regime.70 As set out in Article 2(3) of the CTR, this category covers trials with already authorized investigational medicinal products (excluding placebos) that are used either in accordance with the marketing authorization or in a manner that is evidence-based, supported by published scientific evidence on the safety and efficacy of the product,71 and that involve “additional diagnostic or monitoring procedures [that] do not pose more than minimal additional risk or burden to the safety of the subjects compared to normal clinical practice in any Member State concerned.”

The last minimal risk requirement contains comparative language that could suggest a relative interpretation of the threshold. However, this is not the intended or appropriate reading of the provision. What should be “compared to normal clinical practice” is not the level of risk associated with additional investigational diagnostic or monitoring procedures, but rather the presence, nature, extent, and frequency of these procedures. Those that go beyond “normal clinical practice” must meet the minimal risk threshold. This is clearly emphasized by the Expert Group on Clinical Trials for the Implementation of the CTR in its 2017 Recommendations on “Risk Proportionate Approaches in Clinical Trials” that read: “[A]dditional risk or burden might include non-invasive procedures as well as invasive procedures (…) if these are performed with a significantly higher frequency or significantly greater intrusiveness, or a larger number of assessments are undertaken compared to normal clinical practice, during a greater number of visits to the clinic/hospital.”72

Thus, the assessment of risk in potentially low-intervention clinical trials focuses on the level of risk associated with trial-related diagnostic or monitoring procedures that are designed and performed solely for scientific purposes and, as such, are not part of the authorized and/or evidence-based use of the particular medicinal product, i.e., are additional to the standard clinical practice. By separating the acceptable level of risk of investigational interventions from the level of risk associated with normal clinical practice, the CTR’s standard of additional minimal net risk does not raise the ethical disanalogy, indeterminacy and exploitation objections.73 And it offers a sought-after alternative for conceptualizing the minimal risk threshold in “non-therapeutic” clinical trials on subjects unable to give consent.74 Participation is such trials cannot add more than minimal risk (and burden) to the level of risk (and burden) associated with the standard treatment of the subjects, if there is one, whatever it is, and if the participants need one at all. In other words, this interpretation suggests the following reading of the threshold: A “non-therapeutic” clinical trial involves only minimal risk if the level of risk of the trial-related procedures is minimal. Unfortunately, this definition is tautological and says little about when such net risks are minimal. As such, it does not provide so much-needed guidance for the REC’s assessment of these risks.

5. When is net risk “minimal”?

As shown, the CTR does not provide an adequate definition of minimal risk, and the comparisons based on the daily living standard and/or the routine examination standard proposed by the European Commission’s expert groups raise more questions than they answer. However, the recommendations of the groups mentioned above provide some interpretative guidance on how the minimal risk threshold should be understood in the form of lists of exemplary interventions that may be considered to pose only minimal risk, when performed once or infrequently, without additional intrusiveness, and in accordance with the highest professional standards.

The longest list of procedures involving “no or minimal risk” (as well as the lists of interventions involving “minor increase above minimal risk” and “greater than minor increase over minimal risk”) was contained in the 2008 Recommendations concerning pediatric studies issued under the repealed Clinical Trials Directive. The list of “no or minimal risk” procedures included: “history taking, clinical examination, auxological measurements, tanner staging, behavioural testing, psychological testing, quality of life assessment, venipuncture, heel prick, finger prick, subcutaneous injection, urine collection with bag, breath condensate collection, collection of saliva or sputum, collection of hair sample, collection of tissue removed from body as part of medical treatment, topical analgesia, stool tests, bio-impedancemetry, transcutaneous oxygen saturation monitoring (pulse oxymetry), blood pressure monitoring, electroencephalography, electrocardiography, vision or hearing testing, ophthalmoscopy, tympanometry, lung function tests (peak flow, exhaled NO, spirometry), oral glucose tolerance test, ultrasound scan, digitally amplified chest or limb X-ray, stable isotope examination.”75

Unlike the 2008 Recommendations, the 2017 Recommendations of the Expert Group on Clinical Trials for the Implementation of the CTR, “Ethical Considerations for Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products Conducted with Minors,” do not provide a risk-based categorization of research interventions. Instead, Annex 3 of the document contains an alphabetical list of procedures frequently conducted for trial-related purposes, accompanied by “description of the elements of risk and burden to be evaluated.”76 The majority of interventions classified as having “no or minimal risk” in the 2008 Recommendations are still described as “no risk” in the 2017 guidance (with the exception of instances where venous access, contrast, sedation, and/or anesthesia are employed). However, while the 2008 Recommendations treated venipuncture, subcutaneous injection, and oral glucose tolerance testing as minimal risk interventions,77 the 2017 Recommendations are less explicit in this regard and appear to indicate that the procedures entail more than minimal risk.

Finally, the 2017 Recommendations on “Risk Proportionate Approaches in Clinical Trials”78, commenting on the concept of low interventional clinical trials introduced by the CTR, give the following examples of minimal risk diagnostic or monitoring interventions: “measuring height and/or weight, questionnaires, analysis of saliva, urine, stool samples, EEG and ECG measurements, blood withdrawal through a pre-existent catheter or with minimal additional venipuncture.”79

Notwithstanding minor discrepancies between the lists, they are a valuable source of information for researchers and RECs on what constitutes a minimal risk research procedure.80 Thus, although they are not exhaustive and “should not be used dogmatically,”81 they are a useful starting point for assessing the risks and burdens associated with a “non-therapeutic” clinical trial involving participants who are unable to give consent. More importantly, they all seem to reflect the general moral intuition “that research risks are minimal when the risk of serious harm is very unlikely and the potential harms associated with more common adverse events are small.”82

This intuition also underpins the Council of Europe’s definition of the minimal risk threshold, although it has been badly phrased in the Additional Protocol to the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine concerning Biomedical Research. Article 17.1 of the Protocol stipulates that “the research bears a minimal risk if, having regard to the nature and scale of the intervention, it is to be expected that it will result, at the most, in a very slight and temporary negative impact on the health of the person concerned.”83 Evidently, the definition tries to protect participant of “non-therapeutic” research unable to give consent from any serious and moderate harm. Unfortunately, by considering only the severity of the expected harm and completely ignoring the likelihood of its occurrence, it literally excludes almost all such studies.84 It is because in the context of scientific research, it is impossible to be certain that a given investigational procedure poses no chance of significant harm.85 Thus, the definition establishes a harm threshold rather than a risk threshold. Furthermore, by focusing on harms to subjects’ health, it ignores other interests of research participants deserving protection.

The deficiencies in the Council of Europe’s definition of the minimal risk threshold are not trivial, but they are not intentional. This is evident from the Explanatory Report to the Additional Protocol on Biomedical Research, which comments on the threshold and lists examples of minimal risk (and minimal burden) procedures. The list includes a large number of procedures that have a very low, but still greater than “zero” probability of causing more than minor harm. Examples include procedures (also found on the EU expert group lists) such as: „obtaining bodily fluids without invasive intervention, e.g., taking saliva or urine samples or cheek swab,” “taking a blood sample from a peripheral vein or taking a sample of capillary blood,” taking small additional tissue samples “at the time when tissues samples are being taken, for example during a surgical operation,” and “minor extensions to non-invasive diagnostic measures using technical equipment, such as sonographic examinations, taking an electrocardiogram following rest.”86 Moreover, the Explanatory Report also classifies as minimal risk “one X-ray exposure,” “carrying out one computer tomographic exposure or one exposure using magnetic resonance imaging without a contrast medium,”87 i.e., procedures that were explicitly mentioned by the EU 2008 Recommendations as involving minor increase over minimal risk.88

In summary, despite the small differences between the Council of Europe and EU regulations and/or recommendations regarding minimal risk in “non-therapeutic” studies, both European organizations share the view89 that research without the prospect of direct benefit should not be permitted on persons unable to give consent if there is a significant chance of more than minor harm. And this view supports the following understanding of the minimal risk threshold under the CTR: A “non-therapeutic” clinical trial involves only minimal risk if the likelihood that the trial-related procedures will cause serious and/or moderate harm is, at most, very low, and the likelihood of small harm (i.e., very slight and temporary harm) has been adequately minimized.

The above threshold is not strictly defined because it should not be. The evaluation of research risk cannot be fixed because it depends very much on circumstances related to the nature, design and context of the trial procedures as well as the characteristics of the trial population. Thus, there must always be room for deliberative, critical, and careful ethical reflection on the acceptability of research risk, which the above definition leaves open. However, in order to provide researchers and REC members with sufficiently clear guidance for risk assessment, the definition should be used in conjunction with the list of examples. Such a list of examples of minimal risk procedures should be developed and regularly updated on the basis of available empirical data and expert opinion.90

6. Concluding remarks

The CTR adopts the internationally well-known minimal risk (and burden) requirement for “non-therapeutic” clinical trials involving selected vulnerable populations, particularly minors and incompetent subjects. The threshold is considered to strike an appropriate balance between the interests and rights of such persons – in particular their rights not to be instrumentalized contrary to their dignity and to have their physical and mental integrity adequately protected – and the societal interest in the advancement of biomedical science and practice.91 However, the wording of the threshold is so ambiguous and confusing that can easily be interpreted in ways that are unethical and inconsistent with the overall goals of the CTR. This paper offers an alternative reading of the standard in such trials, in the hope that it will be taken into account by the clinical research community and by the European and national authorities responsible for the implementation of the CTR. While the CTR has been approved and cannot be easily amended, related documents, such as the 2017 Recommendations on “Ethical Considerations for Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products Conducted with Minors,” can be revised to provide more appropriate guidance on the threshold. Such changes would not only protect vulnerable participants in “non-therapeutic” clinical trials from excessive risk and exploitation, but would also ensure greater consistency and accountability in the opinions of the RECs on the acceptable level of risk in “non-therapeutic” clinical trials involving such participants.

European Union (2014). ↑

The CTR provides a 3-year transition period for clinical trials approved under the Clinical Trial Directive. From January 31, 2025, all ongoing trials authorized under the Directive must comply with the CTR and be recorded in the Clinical Trials Information System. ↑

EMA (2023). ↑

See for example Westra et al. (2014); Mittica, Pfisterer (2015); Abou-El-Enein, Schneider (2016); Flear (2016); Giannuzzi et al. (2016); Gefenas et al. (2017); Tenti et al. (2018); Scavone et al. (2019); Knaapen et al. (2020); Kim, Hasford (2020); Lukaseviciene et al. (2021). ↑

European Union (2001). ↑

The term “subject” is still used in EU clinical trial legislation, although there is a growing consensus in the ethics literature and the international research community that it should be replaced by the more respectful term “participant.” However, in order to remain consistent with the wording of the EU regulations, I will use these two terms in this paper, treating them as synonyms. ↑

The label “non-therapeutic trial” has been rightly criticized by some authors for implying – against the goals and nature of the research practice – that there are also “therapeutic” trials and for contributing to the phenomenon of therapeutic misconception. For the sake of brevity and clarity, however, I will use this term in this paper. I find it less confusing in the context of the analysis that follows than the alternative term “non-beneficial trial.” ↑

For more on peer benefit, see Johansson, Broström (2012). ↑

Lenaerts, Gutiérrez-Fons (2013); Gambos (2014); Brannon (2018). ↑

Ibidem. ↑

Ibidem. ↑

Gennet, Altavilla (2016); Westra (2016); Wade (2017). ↑

See Bartholome (1976); Ackerman (1980); Redmon (1986); Kopelman (2004a, 2012); Litton (2008, 2012); Wendler (2010, 2012); Spriggs (2012); Shah (2013); Broström, Johansson (2014); Piasecki et al. (2015); DeGrazia et al. (2017); Binik (2018); Różyńska (2022). ↑

Nuremberg Military Tribunal (1947). ↑

WMA (1964, 1975, 1983, 1989, 1996). It is important to note that the original 1964 version of the Declaration included two conflicting provisions regarding the participation of legally incompetent subjects in “non-therapeutic clinical research.” Paragraph III.3a stated: „Clinical research on a human being cannot be undertaken without his free consent after he has been informed; if he is legally incompetent, the consent of the legal guardian should be procured.” While paragraph III.3b read: „The subject of clinical research should be in such a mental, physical and legal state as to be able to exercise fully his power of choice.” ↑

See Jonsen (2006). ↑

McCormick (1974, 1976). ↑

Ramsey (1976, 1977) ↑

Ramsey (1970): 12–13. ↑

Shirkey (1968). ↑

Mastroianni, Kahn (2001); Alexander (2002); Ross, Coffey (2002); Ross (2004, 2006); Saint Raymond, Brasseur (2005); DuBois et al. (2012); Helmchen et al. (2014). ↑

For example, in order to stimulate and facilitate the development and availability of the high quality and authorized medicines for children across Europe, the EU adopted Regulation (EC) No 1901/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2006 on medicinal products for paediatric use and amending Regulation (EEC) No 1768/92, Directive 2001/20/EC, Directive 2001/83/EC and Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 (so called the “Paediatric Regulation”). See also Labson (2002); Gill (2004); Rose (2014). ↑

Kopelman (2004b). ↑

Due to space limitations, this paper focuses on the concept of minimal risk, leaving the specific problems of defining minimal burden for another occasion. See further Westra et al. (2010), Westra et al. (2011). ↑

WMA (2024). For the very first time the minimal risk threshold appeared in the 2008 revision of the Declaration (par. 27; WMA 2008). See also WMA (2013, par. 28). ↑

UNESCO (2005). ↑

CIOMS (2016). ↑

Council of Europe (1997a), Article 17(2)ii; Council of Europe (1997b), paras. 111, 113. ↑

Council of Europe (2005a), Article 15(2)ii; Council of Europe (2005b), paras. 96-100. ↑

ICH (2016) ↑

Most likely, the drafters of ICH-GCP chose the word “low” to make the standard compatible with U.S. federal regulations, which allow “non-therapeutic” pediatric clinical research involving “minimal risk” as well as those involving “a minor increase over minimal risk.” (The author thanks an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.) ↑

Pinxten et al. (2011). To compare European regulations on pediatric clinical trials, see Altavilla (2008); Buchner, Hart (2008); Canellopoulou-Bottis (2008); Junod (2008); although Switzerland is not a member states of the EU, its law on medical research complied with EU legislation, in particular Directive 2001/20/EC; Lötjönen (2008); Nys et al. (2008); Sheikh (2008). ↑

Article 4(e) of the Clinical Trials Directive provided that clinical trials on minors could be conducted if “some direct benefit to the group of patients” was to be obtained. And the term “group of patients” was open to two contradictory interpretations. It could have been interpreted as referring to sick minor participants in a given trial, thus prohibiting “non-therapeutic” pediatric trials, or as referring to children as a group of potential patients, thus allowing such trials. See also Wade (2017). ↑

Pinxten et al. (2011); Andorno (2010). ↑

European Commission (2008). ↑

Common Rule (1991/2018): 45 CFR §46.102(j), 45 CFR §46.406, 45 CFR §46.407. ↑

European Commission (2008): 18. ↑

Ibidem. Practical examples for all risk categories were presented in Annex 4. ↑

Kopelman (2004b). ↑

Freedman et al. (1993); Barnbaum (2002); Kopelman (2000; 2004b); Resnik (2005, 2014); Wendler (2005); Wendler et al. (2005); Ross (2006); Ross, Nelson (2006); Wendler, Glantz (2007); Snyder et al. (2011); Binik (2014, 2017); Binik et al. (2011); Binik, Weijer (2014); Rid (2014); DeGrazia et al. (2017); Rossi, Nelson (2017); Kwek (2024). ↑

Kopelman (2000; 2004b). ↑

It is worth noting that the absolute interpretation of the minimal risk standard was originally adopted by the U.S. National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects in Biomedical and Behavioral Research (1977). The definition of minimal risk proposed by the Commission referred to “the probability and magnitude of physical or psychological harm that is normally encountered in the daily lives, or in the routine medical or psychological examination, of healthy children” (National Commission 1977, p. xix; emphasis added). However, the “healthy” qualifier was removed when the Commission’s recommendations were converted into regulations, out of fear that valuable research would be banned. (The author thanks an anonymous reviewer for pointing that out.) ↑

NHRPAC (2002): 1–2. ↑

IOM (2004): 121–126. ↑

SACHRP (2005; 2008). ↑

FDA (2022): 4. ↑

SACHRP (2005). See also NHRPAC (2002): 1–2; IOM (2004): 126; FDA (2022): 4. ↑

Ibidem. ↑

Kopelman (2000); Wendler, Emanuel (2005); Iltis (2007); Wendler (2013). See also IOM (2004): 126–134; SACHRP (2005); FDA (2022): 5. ↑

European Commission (2008): 19. ↑

Westra et al. (2010). ↑

Council of Europe (2005b), para. 96. ↑

European Commission (2017a). ↑

Gennet, Altavilla (2016); Westra (2016); Wade (2017). ↑

WHO (2018). ↑

European Commission (2017a): 22–23. ↑

Ibidem. ↑

Macklin, Natanson (2020). ↑

See Lurie, Wolfe (1997); Resnik (1998); Schüklenk (1998); Macklin (2004). ↑

European Commission (2017a): 12–13. ↑

Ibidem: 13. ↑

E.g. IOM (2004); SACHRP (2005, 2008); FDA (2022). ↑

CIOMS (2016): 12. ↑

Wendler (2005). ↑

Simonsen (2012); Rid (2014); Różyńska (2023). ↑

Lenk et al. (2004); Shah et al. (2004); Van Luijn et al. (2006). ↑

Simonsen (2012); Rid (2014); Różyńska (2023). ↑

Resnik (2005); Westra et al. (2010, 2011); Rid (2014); Wade (2017). ↑

Simonsen (2012): 199; Wade (2017). ↑

Knaapen et al. (2020). ↑

„The published scientific evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of an IMP [investigational medicinal product –Author] which is not used in accordance with the terms of the marketing authorisation could include evidence based treatment guidelines, health technology assessment reports, and clinical trial data published in scientific peer reviewed journals or other appropriate evidence”; see European Commission (2017b): 5. ↑

Ibidem: 5. ↑

The idea of separately assessing the risks associated with procedures conducted solely for research purposes is based on the logic of so-called component (or single-intervention) risk analysis. Component analysis differs from an overall risk-benefit assessment, in which the combined interventions and procedures of a study (the entire protocol) are evaluated as a whole. Component analysis recognizes that a research protocol often contains a mixture of procedures and interventions, each of which may have different risks and may or may not provide direct benefit to study participants. To determine the overall acceptability of the study, component analysis requires a careful ethical evaluation of the various components (procedures and interventions) of the protocol, first individually and then collectively. For a discussion of different models of component analysis, see Weijer (1999, 2000); Weijer, Miller (2004, 2007); Wendler, Miller (2007); Rid, Wendler (2010, 2011a); Rid (2012). In the context of pediatric research, see FDA (2022): 7–8. ↑

This way of thinking is also present in the 2017 Recommendations: „Where a procedure is conducted as part of standard of care, there is no trial-related risk or burden”, European Commission (2017a), p. 35. ↑

European Commission (2008): 30. ↑

European Commission (2017a): 35. ↑

The 2008 Recommendations noted, however, that the risk evaluation of these procedures is highly dependent on a number of factors, including the circumstances, frequency, and susceptibility to harm of the organ exposed or involved. Additionally, the context of their use in the trial must be taken into account. European Commission (2008): 30. ↑

European Commission (2017b). ↑

Ibidem: 5. ↑

Exemplary lists of minimal risk procedures can also be found in U.S. recommendations, see IOM (2004): 135 (table); SACHRP (2005); FDA (2022): 5. ↑

European Commission (2017a): 35. ↑

CIOMS (2016): 12. ↑

It is worth noting that the Additional Protocol also defines “minimal burden” as “discomfort associated with participation in the research, which is expected to be at most temporary and very slight for the person concerned” (Article 17.2). ↑

Rid (2012, 2014); Wendler (2005); Wendler, Glantz (2007). ↑

Council of Europe (2005b), para. 100. ↑

Ibidem. ↑

Ibidem. ↑

This does not apply to a digitally amplified chest or limb X-ray, which is consider a minimal risk procedure. European Commission (2008): 30. ↑

For ethical justification of the view see Różyńska (2022). ↑

For suggestions on how to develop and update a list of minimal risk interventions (a research risk repository), see, for example, Glantz (1998); Rid, Wendler (2011b); Wade (2017). For suggestions on how to categorize magnitude and likelihood of harm, see, for example, Rid et al. (2010); Westra et al. (2011). ↑

European Union (2014), Articles 3 and 28; cf. Council of Europe (1997a), Articles 1 and 2; Council of Europe (1997b), esp. para. 111; Council of Europe (2005a), Articles 1 and 3; Council of Europe (2005b), esp. paras. 12, 13, 96. See also Różyńska (2022). ↑

Funding: This research was funded by the National Science Centre, Poland, grant no. 2023/50/E/HS1/00486.

Acknowledgments: I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their careful reading of my manuscript and their insightful comments and suggestions, which help me to improve the paper and to better understand the historical debates and current U.S. regulations and recommendations regarding the minimal risk standard in clinical research.

Conflict of Interests: The author declares no conflict of interest.

License: This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abou-El-Enein M., Schneider C.K. (2016), “Deciphering the EU clinical trials regulation,” Nature Biotechnology 34 (3): 231–233.

Ackerman T.F. (1980), “Moral duties of parents and nontherapeutic clinical research procedures involving children,” Bioethics Quarterly 2 (2): 94–111.

Alexander D. (2002), “Regulation of research with children: The evolution from exclusion to inclusion,” Journal of Health Care Law & Policy 6 (1): 1–13.

Altavilla A. (2008), “Clinical research with children: the European legal framework and its implementation in French and Italian law,” European Journal of Health Law 15 (2): 109–125.

Andorno R. (2010), “Regulatory discrepancies between the Council of Europe and the EU regarding biomedical research,” [in:] Human Rights and Biomedicine, A. den Exter (ed.), Maklu Press, Antwerp: 117–133.

Barnbaum D. (2002), “Making more sense of ‘minimal risk’,” IRB: Ethics & Human Research 24 (3): 10–13.

Bartholome W.G. (1976), “Parents, children, and the moral benefits of research,” The Hastings Center Report 6 (6): 44–45.

Binik A. (2014), “On the minimal risk threshold in research with children,” The American Journal of Bioethics 14 (9): 3–12.

Binik A. (2017), “A defense of the-risks-of-daily-life,” Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 27 (3): 413–442.

Binik A. (2018), “Does benefit justify research with children?,” Bioethics 32 (1): 27–35.

Binik A., Weijer C. (2014), “Why the debate over minimal risk needs to be reconsidered,” Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 39 (4): 387–405.

Binik A., Weijer C., Sheehan M. (2011), “Minimal risk remains an open question,” The American Journal of Bioethics 11 (6): 25–27.

Broström L., Johansson M. (2014), “Involving children in nontherapeutic research: On the development argument,” Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 17 (1): 53–60.

Brannon V. C. (2018), Statutory Interpretation: theories, tools, and trends, Congressional Research Service Report R45153, URL = https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45153 [Accessed 12.06.2024].

Buchner B., Hart D. (2008), “Research with minors in Germany,” European Journal of Health Law 15 (2): 127–134.

Canellopoulou-Bottis M. (2008), “Research with minors in Greece and the EU Directive on clinical trials,” European Journal of Health Law 15 (2): 163–168.

CIOMS (Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences) (2016), International Ethical Guidelines for Health-Related Research Involving Humans, Geneva, URL = https://cioms.ch/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/WEB-CIOMS-EthicalGuidelines.pdf [Accessed 12.06.2024].

Common Rule (1991/2018), the US Code of Federal Regulations, Title 45, Part 46 Protection of Human Subjects, URL = https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-45/subtitle-A/subchapter-A/part-46?toc=1 [Accessed 12.06.2024].

Council of Europe (1997a), Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine. Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, ETS 164, URL = https://rm.coe.int/168007cf98 [Accessed 12.06.2024].

Council of Europe (1997b), Explanatory Report to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine. Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, URL = https://rm.coe.int/16800ccde5 [Accessed 12.06.2024].

Council of Europe (2005a), Additional Protocol to the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine concerning Biomedical Research, CETS 195, URL = https://rm.coe.int/168008371a [Accessed 12.06.2024].

Council of Europe (2005b), Explanatory Report to the Additional Protocol to the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine concerning Biomedical Research, URL = https://rm.coe.int/16800d3810 [Accessed 12.06.2024].

DeGrazia D., Groman M., Lee L.M. (2017), “Defining the boundaries of a right to adequate protection: A new lens on pediatric research ethics,” Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 42 (2): 132–153.

DuBois J.M., Beskow L., Campbell J., Dugosh K., Festinger D., Hartz S., James R., Lidz C. (2012), “Restoring balance: A consensus statement on the protection of vulnerable research participants,” The American Journal of Public Health 102 (12): 2220–2225.

EMA (European Medicine Agency) (2023), Clinical Trials Regulation, URL = https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-regulation [Accessed 12.06.2024].

European Commission (2008), Ethical Considerations for Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products Conducted with the Paediatric Population. Recommendations of Ad Hoc Group for the Development of Implementing Guidelines for Directive 2001/20/EC relating to Good Clinical Practice in the Conduct of Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products for Human Use, URL = https://ec.europa.eu/health//sites/health/files/files/eudralex/vol-10/ethical_considerations_en.pdf [Accessed 12.06.2024].

European Commission (2017a), Ethical Considerations for Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products Conducted with Minors. Recommendations of the Expert Group on Clinical Trials for the Implementation of Regulation (EU) No 536/2014 on Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products for Human Use, URL = https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/d721d6cb-687a-477f-b40f-8c7922e9ec9a_en [Accessed 12.06.2024].

European Commission (2017b), Risk Proportionate Approaches in Clinical Trials. Recommendations of the Expert Group on Clinical Trials for the Implementation of Regulation (EU) No 536/2014 on Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products for Human Use, URL = https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2017-08/2017_04_25_risk_proportionate_approaches_in_ct_0.pdf [Accessed 12.06.2024].

European Union (2001), Directive 2001/20/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 April 2001 on the Approximation of the Laws, Regulations and Administrative Provisions of the Member States Relating to the Implementation of Good Clinical Practice in the Conduct of Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products for Human Use, Official Journal of the European Union L 121 (44): 34–44 with further amendments. Consolidated text: URL = https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2001/20/2022-01-01 [Accessed 12.06.2024].

European Union (2006), Regulation (EC) No 1901/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2006 on Medicinal Products for Paediatric Use and Amending Regulation (EEC) No 1768/92, Directive 2001/20/EC, Directive 2001/83/EC and Regulation (EC) No 726/2004, Official Journal of the European Union L 378 (1): 1–19, URL = https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2006/1901/oj [Accessed 12.06.2024].

European Union (2014), Regulation (EU) 536/2014 on of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products for Human Use, and Repealing Directive 2001/20/EC, Official Journal of the European Union L 158 (57): 1–76 with further amendments. Consolidated text: URL = https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2014/536/2022-12-05 [Accessed 12.06.2024].

FDA (Food and Drug Administration) (2022), Ethical Considerations for Clinical Investigations of Medical Products Involving Children; Draft Guidance for Industry, Sponsors, and Institutional Review Boards, URL = https://www.fda.gov/media/161740/download [Accessed 18.12.2024].

Flear M.L. (2016), “The EU Clinical Trials Regulation: key priorities, purposes and aims and the implications for public health,” Journal of Medical Ethics 42 (3): 192–198.

Freedman B., Fuks A., Weijer C. (1993), “In loco parentis: minimal risk as an ethical threshold for research upon children,” Hastings Center Report 23 (2): 13–19.

Gambos K. (2014), “EU Law viewed through the eyes of a national judge,” The European Commission’s Legal Service Seminar Paper, URL = https://web.archive.org/web/20211123102230/https://ec.europa.eu/dgs/legal_service/seminars/20140703_gombos_speech_en.pdf [Accessed 12.06.2024].

Gefenas E., Cekanauskaite A., Lekstutiene J., Lukaseviciene V. (2017), “Application challenges of the new EU Clinical Trials Regulation,” European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 73: 795–798.

Gennet É., Altavilla A. (2016), “Paediatric research under the new EU Regulation on clinical trials: Old issues new challenges,” European Journal of Health Law 23: 325–349.

Giannuzzi V., Altavilla A., Ruggieri L., Cecci A. (2016), “Clinical trial application in Europe: what will change with the new regulation?,” Science and Engineering Ethics 22 (2): 451–466.

Gill D. (2004), “Ethical principles and operational guidelines for good clinical practice in paediatric research. Recommendations of the Ethics Working Group of the Confederation of European Specialists in Paediatrics (CESP),” European Journal of Pediatrics 163: 53–57.

Glantz L.H. (1998), “Research with children,” American Journal of Law & Medicine 24 (2–3): 213–244.

Helmchen H., Hoppu K., Stock G., Thiele F., Vitiello B., Weimann A. (2014), From exclusion to inclusion: Improving clinical research in vulnerable populations. Memorandum, Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities, URL = https://edoc.bbaw.de/opus4-bbaw/frontdoor/index/index/docId/2290 [Accessed 12.06.2024].

ICH (International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use) (2016), ICH Harmonised Guideline Integrated Addendum to ICH E6 (R1): Guideline For Good Clinical Practice E6 (R2), URL = https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/E6_R2_Addendum.pdf [Accessed 12.06.2024].

Iltis A. (2007), “Pediatric research posing a minor increase over minimal risk and no prospect of direct benefit: challenging 45 CFR 46.406,” Accountability in Research 14 (1): 19–34.

IOM (Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, Committee on Clinical Research Involving Children, Board on Health Sciences Policy) (2004), Ethical Conduct of Clinical Research Involving Children, M. J. Field, R.E. Behrman (eds.), The National Academy Press, Washington D.C., URL= https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/10958/ethical-conduct-of-clinical-research-involving-children [Accessed 12.06.2024].

Johansson M., Broström L. (2012), “Does peer benefit justify research on incompetent individuals? The same-population condition in codes of research ethics,” Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 15: 287–294.

Jonsen A.R. (2006), “Nontherapeutic research with children: The Ramsey versus McCormick debate,” The Journal of Pediatrics 149 (1): S12–S14.

Junod V. (2008), “The Swiss regulatory framework for paediatric health research,” European Journal of Health Law 15 (2): 183–195.

Kim D., Hasford J. (2020), “Redundant trials can be prevented, if the EU clinical trial regulation is applied duly,“ BMC Medical Ethics 21: 1–19.

Knaapen M., Ploem M.C., Kruijt M., Oudijk M.A., van der Graff R., Bet P.M., Bakx P., van Heurn L.W.E., Gorter R.R., van der Lee J.H. (2020), “Low-risk trials for children and pregnant women threatened by unnecessary strict regulations. Does the coming EU Clinical Trial Regulation offer a solution?,” European Journal of Pediatrics 179: 1205–1211.

Kopelman L.M. (2000), “Moral problems in assessing research risk,” IRB: Ethics & Human Research 22: 3–7.

Kopelman L.M. (2004a), “What conditions justify risky nontherapeutic or “no benefit” pediatric studies: A sliding scale analysis,” Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 32 (4): 749–758.

Kopelman L.M. (2004b), “Minimal risk as an international standard in research,” Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 29 (3): 351–738.

Kopelman L.M. (2012), “On justifying pediatric research without the prospect of clinical benefit,” The American Journal of Bioethics 12 (1): 32–34.

Kwek A. (2024), “The ‘risks of routine tests’ and analogical reasoning in assessments of minimal risk,” The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 49 (1): 102–111.

Labson M.S. (2002), “Pediatric priorities: legislative and regulatory initiatives to expand research on the use of medicines in pediatric patients,” Journal of Health Care Law & Policy 6 (1): 34–71.

Lenaerts K., Gutiérrez-Fons J.A. (2013), “To say what the law of the EU is: Methods of interpretation and the European Court of Justice,” European University Institute-Academy of European Law: EUI Working Paper AEL 2013/9, URL = https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/28339/AEL_2013_09_DL.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Accessed 12.06.2024].

Lenk C., Radenbach K., Dahl K.M., Wiesemann C. (2004), “Non-therapeutic research with minors: how do chairpersons of German research ethics committees decide?,” Journal of Medical Ethics 30: 85–87.

Litton P. (2008), “Non-beneficial pediatric research and the best interests standard: A legal and ethical reconciliation,” Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law & Ethics 8 (2): 359–420.

Litton P. (2012), “A more persuasive justification for pediatric research,” The American Journal of Bioethics, 12 (1): 44–46.

Lötjönen S. (2008), “Medical research on minors in Finland,” European Journal of Health Law 15 (2): 135–144.

Lukaseviciene V., Hasford J., Lanzerath D., Gefenas E. (2021), “Implementation of the EU Clinical Trial Regulation transforms the ethics committee systems and endangers ethical standards,” Journal of Medical Ethics 47 (12): e82–e82.

Lurie P., Wolfe S. (1997), “Unethical trials of interventions to reduce perinatal transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus in developing countries,” NEJM 337: 853–856.

Macklin R. (2004), Double Standards in Medical Research in Developing Countries, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Macklin R., Natanson C. (2020), “Misrepresenting ‘usual care’ in research: an ethical and scientific error,” The American Journal of Bioethics 20 (1): 31–39.

Mastroianni A., Kahn J. (2001), “Swinging on the pendulum: shifting views of justice in human subjects research,” Hastings Center Report 31 (3): 21–28.

McCormick R.A. (1974), “Proxy consent in the experimentation situation,” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 18 (1): 2–23.

McCormick R.A. (1976), “Experimentation in children: sharing in sociality,” Hastings Center Report 6 (6):41–46.

Mittica G., Pfisterer J. (2015), “The hurdles of conducting clinical trials across different countries: focus on new European regulations,” Cancer Breaking News 3 (2): 44–46.

National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects in Biomedical and Behavioral Research (1977), Research Involving Children. Report and Recommendations, U.S. Govern- ment Printing Office, Washington, D.C., URL = https://videocast.nih.gov/pdf/ohrp_research_involving_children.pdf [Accessed 12.06.2024].

NHRPAC (National Human Research Protections Advisory Committee) (2002), Clarifying Specific Portion of 45 CFR 46 Subpart D That Governs Children’s Research, URL = https://wayback.archive-it.org/4657/20150930183548/http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/archive/nhrpac/documents/nhrpac16.pdf [Accessed 18.12.2024].

Nuremberg Military Tribunal (1947), The Nuremberg Code (United States vs. Karl Brandt, et al. Nov. 21, 1946 - Aug. 20, 1947), [in:] Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law no. 10, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 1946-1949, vol. II: 181–182, URL = https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-01130400RX2-mvpart [Accessed 12.06.2024].

Nys H., Dierickx K., Pinxten W. (2008), “The implementation of Directive 2001/20/EC into Belgian law and the specific provisions on pediatric research,” European Journal of Health Law 15 (2): 153–161.

Piasecki J., Waligóra M., Dranseika V. (2015), “Non-beneficial pediatric research: individual and social interests,” Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 18 (1): 103–112.

Pinxten W., Dierickx K., Nys H. (2011), “Diversified harmony: Supranational and domestic regulation of pediatric clinical trials in the European Union,” Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 10: S183–S198.

Ramsey P. (1970), The Patient as Person, Yale University Press, New Haven.

Ramsey P. (1976), “The enforcement of morals: Non-therapeutic research on children,” Hastings Center Report 6 (4): 21–30.

Ramsey P. (1977), “Children as research subjects: A reply,” Hastings Center Report 7 (2): 40–41.

Redmon R.B. (1986), “How minors can be respected as ends yet still be used as subjects in non-therapeutic research,” Journal of Medical Ethics 12 (2): 77–82.

Resnik D.B. (1998), “The ethics of HIV research in developing nations,” Bioethics 12: 286–306.

Resnik D.B. (2005), “Eliminating the daily life risks standard from the definition of minimal risk,” Journal of Medical Ethics 31 (1): 35–38.

Resnik D.B. (2014), “Making sense of the undue burden interpretation of minimal risk,” The American Journal of Bioethics 14 (9): 1–2.

Rid A. (2012), “Risk and risk-benefit evaluations in biomedical research,” [in:] Handbook of Risk Theory. Epistemology, Decision Theory, Ethics, and Social Implications of Risk, S. Roeser, R. Hillerbrand, P. Sandin, M. Peterson (eds.), Springer, Dordrecht: 179–211.

Rid A. (2014), “Setting risk thresholds in biomedical research: lessons from the debate about minimal risk,” Monash Bioethics Review 32: 63–85.

Rid A., Emanuel E.J., Wendler D. (2010), “Evaluating the risks of clinical research,” JAMA 304 (13): 1472–1479.

Rid A., Wendler D. (2010), “Risk-benefit assessment in medical research – critical review and open questions,” Law, Probability and Risk 9: 151–177.

Rid A., Wendler D. (2011a), “A framework for risk-benefit evaluations in biomedical research,” Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 21 (2): 141–179.

Rid A., Wendler D. (2011b), “A proposal and prototype for a research risk repository to improve the protection of research participants,” Clinical Trials 8 (6): 705–715.

Rose K. (2014), “Pediatric pharmaceutical legislation in the USA and EU and their impact on adult and pediatric drug development,” [in:] Pediatric Formulations, D. Bar-Shalom, K. Rose (eds.), Springer, New York: 405–419.