*Institute of Philosophy, University of Silesia in Katowice email: tomasz.kubalica@us.edu.pl

**Institute of Political Sciences, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn email: michal.lyszczarz@uwm.edu.pl

This article presents the results of a quantitative and qualitative analysis of retraction notices from philosophy journals with global reach. The analysis is based on the Retraction Watch Database and carried out with respect to the recommendations of the Committee on Publication Ethics. In quantitative terms, the sample consists of only 0.48% of the records in the entire database. Hence, the statistics of publication retractions presented here can only form the basis for a case study. The article attempts to lay out the most common reasons for the retraction of philosophy articles following the typology presented in COPE documents. Our systematic approach shows that the normative regulation of publication retraction should be considered inadequate for the publishing practice in philosophy.

Keywords: Retraction, philosophy, research ethics, Retraction Watch Database, Committee on Publication Ethics

It may prove challenging to find norms for retracting publications that originate directly from the regulations issued by institutions overseeing scientific activity. Scientific publications are an integral part of the global scientific output. Therefore, the retraction of publications – as well as their acceptance – is subject to norms developed within the global legal order. These norms have been introduced into the regulations governing scientific activity by the editors of journals, publishing houses and evaluation bodies.

The primary source of standards for publication are the guidelines of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE), an Anglo-American non-profit organisation dedicated to establishing best practices in the ethics of scientific publishing.1 COPE’s influence stems mainly from its educational activities, through which the committee educates, provides resources and promotes good publication practices. COPE’s counterpart for medical publications is the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). Polish scientific publishers and editors of scientific journals ensure that the published texts comply with the principles set by COPE or ICMJE codes of scientific ethics. Adherence to ethical recommendations demonstrates the integrity of the work of the journal editors. What is crucial, however, is not the mere declaration of adherence to the guidelines but their application, which manifests itself, for example, in the way the scientific editorial office reacts to violations of scientific ethics. The retraction of a publication is the final step that aims to remedy the actual and potential damage that has occurred or may occur due to the publication of a text that violates the principles of scientific integrity. Applying this action is necessary when cases of scientific dishonesty have not been diagnosed for various reasons at the article evaluation and editorial stages.

The normative source of recommendations on retraction is the COPE retraction guidelines issued in 2019.2 COPE’s recommendations highlight the scientific importance of correcting the literature for research flaws and lapses in research ethics. As recently as 2012, only 65% of top scientific journals applied retraction.3 The lack of proper correction of errors and distortions led to many of them being perpetuated, contributing to a decline in the authority of scientific knowledge.

Most questionable is the quality of published retraction notices. The authors of an earlier analysis from 2018 found that between 3% and 18% of the notices did not give any apparent reason for the retraction.4 Many notices were vague or perfunctory. In addition, the retraction of publications was not always carried out appropriately, i.e., with proper reference to the original, albeit withdrawn, work. This means that knowledge of retraction is not widespread and that the article may still be the basis for further citations. Worse still, a carelessly prepared retraction procedure may be the basis for questioning the reasons for the rejection of a text. This often results in the creation of various conspiracy theories (e.g., about the alleged toxicity of vaccines5), the common denominator of which is to question the truth and the authorities’ positions.

The Retraction Watch Database (RWD) is a collection of data on current retractions. The database was created under the auspices of the Retraction Watch science blog, set up in 2010 by Ivan Oransky and Adam Marcus and supported by the US-based Centre for Scientific Integrity (CSI). The blog informs the community about the retraction of scientific papers and related topics.

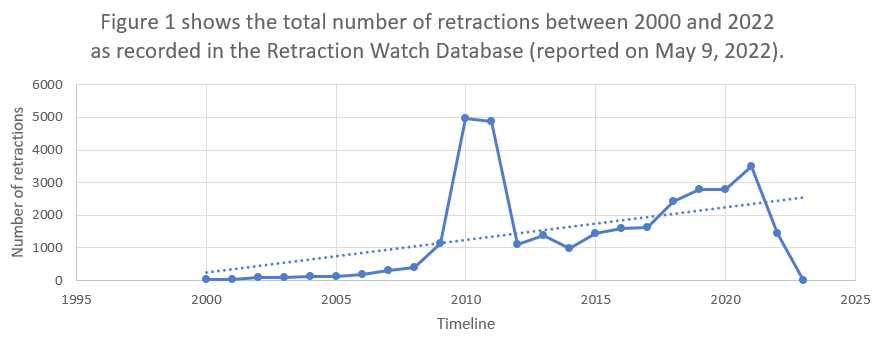

The overall number of retractions has been growing over the past three years. The latest figures from May 9, 2022, show 3,501 retractions in 2021, 2,785 in 2020 and 2,779 in 2019. We searched the RWD database for philosophy on May 9, 2022.6 Our search was exhaustive and provides a good sample for 2022, for it allowed us to compare the last 20 years (33,349 cases) to the whole century (33,843 cases). That said, it is essential to note that the retraction programme is primarily aimed at medical, life and technical sciences. It has only indirectly covered humanities and social sciences due to the new publication policy in science. Hence, the literature on retraction focuses primarily on medical sciences, in line with the guiding principle of responsibility for human life and health. However, there is a lack of quantitative and qualitative analyses of retractions in other sciences, particularly in the humanities and social sciences. The reasons may include the relatively late introduction of codes of professional ethics for representatives of specific disciplines (psychology was a pioneer in this area), lack of universally accepted standards that go beyond declarations; and lack of effectively functioning global regulatory bodies.7

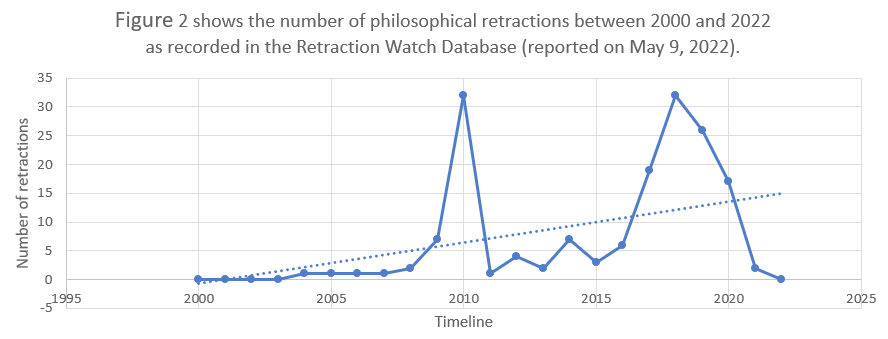

Filling this gap, the study presented here includes an analysis of retractions in philosophy over the last 20 years. Figure 1 shows the total number of retractions between 2000 and 2022. Figure 2 - the number of philosophical retractions over the same period. Figure 1 demonstrates an upward trend with periodic sharp increases and decreases between 2008 and 2012, and a less sharp increase after 2019. Figure 2 is evidence that the retraction curve in philosophy generally replicates the upward trend reflected in Figure 1, but also presents a several-fold increase after 2019. When analysing the retraction graph, it is essential to consider the period between the submission and the publication of the retraction. This period is estimated to be around 18-24 months.8 Accordingly, the trend from at least 18 months ago, i.e., from before 2021, should be examined. Hence, it should not be inferred from Figure 1 that the number of retractions fell sharply after 2021. Many new cases are pending, and the graph does not reflect them. However, it is possible that the COVID-19 pandemic influenced the decline and temporarily hampered research.

The leading search category was philosophy as a subject (Subject) occurring in both the humanities (HUM) and social sciences (SOC). As the creators of the database explained, ‘subject’ means the field of study that is most likely to be referred to or searched for in relation to the information contained in a given article.9 This designation is not disjointed, and many articles tagged as philosophy have overlapping subjects with different prefixes. The database creators do not further specify the procedure for qualifying a given article for a particular scientific discipline, including the subject labelled in the database as ‘philosophy.’ Although that may sometimes be a subjective choice of what the creators consider most relevant, we trusted the authors of the database that their choice was well considered. However, further research on this database should take a more critical approach to the subject matter and look into the role of journal editors in determining the disciplinary scope of articles. There were 30 combinations of ‘philosophy’ as a subject. The subject ‘philosophy’ occurred in 165 records, including 70 records where it came first.10 Publications included in the database often have more than one subject.

Out of 33,845 items in the surveyed material there were 162 records related to philosophy in various configurations with other subjects. The percentage of records related to philosophy was only 0.48%. Such a small sample cannot be considered representative of the whole. If the research could be regarded as conducted on a population-representative statistical sample, it would be possible to formulate statistically valid conclusions about how retractions in philosophy relate quantitatively to the retractions in general. Since the subject is quite new, our conclusions are very cautious and should be taken as general suggestions for further research. Moreover, even that number is exaggerated, as out of 162 retracted articles, 1 contained no information on the reason for withdrawal (+Notice - No/Limited Information), and 40 contained a note with too concise information (+Notice - Limited or No Information). This group is referred to in Table 2 as ‘+Ambiguous notices’.

According to COPE guidelines, the editors should publish a retraction note in the journal’s next issue and refer to the retracted article in the form of a link. Additionally, the original article must remain unchanged and only its electronic version should be watermarked to indicate retraction. Another prerequisite for the correction of the electronic version is the documentation of this fact in the form of the date of the changes and their detailed scope. If the documentation of minor corrections – those which do not affect the scientific results – is different in the digital and paper versions, a correction annotation is mandatory for the digital version. An editorial comment (corrigendum or errata) on the published article with a reference to the original should then be attached to the paper version of the journal. Also, the editors must archive and make all previous versions of the article available.

The retraction notice should contain a minimum of information about the reason for the retraction and be accompagnied by the watermarking of the original as withdrawn. However, the revised text should not contain the corresponding explanation on more than one occasion. In our study, the final number of retractions giving reasons were 121 (0.36% of cases). Due to the negligible proportion of retraction reports for philosophy articles in the total number of reports, the following findings cannot be considered representative of the discipline but only as a case study.

Although it is difficult to consider the quantitative results as representative of philosophy, they are still more extensive than those of the major databases indexing scholarly publications. On November 22, 2022, out of 74.8 million total instances present in the Web of Science Core Collection, there were 660,736 (or 0.88%) units of analysis on philosophy (i.e., classified as ‘philosophy’ by the Web of Science). The corresponding share in the SCOPUS database reaches only 0.64%. Among approximately 84 million records, it contains 538,429 documents with the subject area ‘Arts - philosophy.’

Table 1 shows a ranking of the most common reasons for retracting philosophy articles in the RWD. More than one reason for retraction can apply to a single article.

| Reason | Number of Occurrences |

| +Notice - Limited or No Information | 40 |

| +Plagiarism of Text | 38 |

| +Euphemisms for Plagiarism | 35 |

| +Date of Retraction/Other Unknown | 34 |

| +Breach of Policy by Author | 31 |

| +Investigation by Journal/Publisher | 31 |

| +Plagiarism of Article | 28 |

| +Duplication of Article | 20 |

| +Withdrawal | 11 |

| +Error in Text | 7 |

| +Retract and Replace | 7 |

| +Concerns/Issues about Referencing/Attributions | 6 |

| +Error in Results and/or Conclusions | 6 |

| +Fake Peer Review | 6 |

| +Taken from Dissertation/Thesis | 6 |

| +Duplicate Publication through Error by Journal/Publisher | 5 |

| +Error by Journal/Publisher | 5 |

| +Notice - Lack of | 5 |

| +Paper Mill | 5 |

| +Copyright Claims | 4 |

| +Duplication of Text | 4 |

| +Investigation by Company/Institution | 4 |

| +Unreliable Results | 4 |

| +Concerns/Issues About Results | 3 |

| +Error in Analyses | 3 |

| +Euphemisms for Duplication | 3 |

| +Withdrawn to Publish in Different Journal | 3 |

| +Ethical Violations by Author | 2 |

| +Lack of Approval from Author | 2 |

| +Legal Reasons/Legal Threats | 2 |

| +Concerns/Issues About Authorship | 1 |

| +Concerns/Issues About Data | 1 |

| +Criminal Proceedings | 1 |

| +Error in Methods | 1 |

| +False Affiliation | 1 |

| +Falsification/Fabrication of Data | 1 |

| +Hoax Paper | 1 |

| +Investigation by Third Party | 1 |

| +Lack of Approval from Company/Institution | 1 |

| +Lack of Approval from Third Party | 1 |

| +Misconduct - Official Investigation/Finding | 1 |

| +Objections by Third Party | 1 |

| Notice - No/Limited Information | 1 |

Based on the overview presented above, one can conclude that the categories are blurred and overlap. For example, the most frequently cited reason for retraction is plagiarism. However, this includes five specific reasons (+Plagiarism of Text; +Euphemisms for Plagiarism; +Plagiarism of Article; +Concerns/Issues about Referencing/Attributions; +Concerns/Issues About Authorship), which together account for 108 cases (i.e., 66.7%). However, the possibility of analysing the data is limited by the fact that the most frequently indicated option (as many as 46 indications, i.e., 28.4%) was not linked to any specific reason (+Notice - Limited or No Information; +Notice - Lack of; Notice - No/Limited Information). Given these limitations, it became necessary to use the existing classification of reasons for retracting articles.

There are many reasons why authors, editors or publishers retract scientific papers. More insightful error taxonomies list as many as 12 categories at three levels.11 However, we will limit ourselves to the taxonomy of errors proposed by the creators of the RWD database and relate it to the Retraction Guidelines, as the COPE guidelines apply to publications in Polish science. It is important to remember, however, that the purpose of retraction is to correct the literature and warn readers of errors and unreliability, not to punish authors.12 The institution of retraction has not been set up to discipline or perform a preventive role against abuse, either generally or in a more specific manner.

The COPE document lists various situations when a retraction should occur. There are three types of retraction reasons13:

The first group of reasons is related to erroneous publication content, and the second to scientific dishonesty. Individual torts can coincide. The Committee also recognizes different degrees of dishonesty. Regarding the author(s)’ agency, errors can range from unconscious to intentional: from a simple error to a naive mistake to research fraud.

The first group in the compilation are withdrawals due to seriously flawed or erroneous content or data in their findings and conclusions. Table 2 includes them as notices of errors. In this case a material error is already found in the published work. The work should then be declared invalid and withdrawn with a reason. The category ‘+Error in Text’ indicates an error made in the written part of the article. In the case of the philosophy data (presented in Table 1), this happened seven times. A similar category is the error in results and/or conclusions (‘+Error in Results and/or Conclusions’ – 6 occurrences), an error made in determining the results or establishing the conclusions of an experiment or analysis. Research errors include: ‘+Unreliable Results’ (4 occurrences), when the accuracy or validity of the results is questionable. ‘+Concerns/Issues About Results’ (3 occurrences) refer to any question, controversy or dispute about the validity of the results. ‘+Error in Analyses’ (3 occurrences) – an error made in data evaluation or calculations. The same is true for ‘+Error in Methods’ (1 occurrence), referring to an error made in the experimental protocol, either by using the wrong protocol or by an error during the execution of the protocol.

The error type ‘+Error by Journal/Publisher’ also occurs five times. However, its meaning is ambiguous. In some instances it can mean a withdrawal of articles made by the journal,14 while at other times an error made by the journal or publisher due to, for example, double publication.15

This group should also include the ‘+Paper Mill’ allegation.’ However, the “Retraction Watch Database User Guide Appendix B: Reasons”16 lacks a proper explanation, and this case cannot be analysed with examples in philosophy. An analysis of a selection of articles outside philosophy labelled ‘+Paper Mill’ revealed that the editor-in-chief withdrew these publications due to the authors’ inability to provide raw data to support the conclusions or illustrations presented in the text.

It is challenging to define abuses in publication ethics, as there are many types with varying degrees of significance and, therefore, consequences. Guidelines on Good Publication Practice,17 produced by COPE, is of primary importance here. The document discusses good practices and defines various cases of abuse. It forms the ethical framework for many scientific journals, and its adoption is a prerequisite for indexing a journal in prestigious databases such as SCOPUS. Therefore, the COPE guides also regulate Polish science. As notices of abuse, we included a group of such reasons for retraction in Table 2 (Misconduct notices).

One form of misconduct by the author of a text is the reproduction of particular text or article, often erroneously referred to as ‘self-plagiarism.’ This pseudo-plagiarism occurs when an entire published article or unspecified parts of its text are repeated in another article by the same author without a proper citation. In our database, duplication of the article (‘+Duplication of Article’) occurred 20 times and duplication of text (‘+Duplication of Text’) four times. Such duplication may not be named explicitly and is labelled as ‘+Euphemisms for Duplication’ (3 occurrences) when the announcement does not clearly state that the authors reused ideas, text or images from one of their previously published items without appropriate citation.

The reason labelled ‘+Taken from Dissertation/Thesis’, like ‘+Paper Mill’, is not explained in the “Retraction Watch Database User Guide Appendix B: Reasons.” Unfortunately, it is challenging to analyse examples of its use, as there are no references to these texts in the field of philosophy. However, going back to the retraction of articles outside philosophy, for example, A Discourse Analysis of Quotidian Expressions of Nationalism during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Chinese Cyberspace18 or Modelling and simulation of surfacing welding remanufacturing for tunnel boring machine disc cutter,19 it can be said that “taken from a thesis (dissertation)” means only using a text, the content of which largely overlaps with an already published master’s thesis, doctoral thesis or others.

Also, a duplicate publication error (‘+Duplicate Publication through Error by Journal/Publisher’) may be committed by the editors of a journal or a publisher when the same article is published more than once. This is a technical error, which differs from duplicate publication in that it is not the authors who are at fault for submitting the article twice, but the editors or publishers. This error occurred five times. A more general category of technical error is an error made by a journal editor or publisher, and it also occurred five times. A similar category of retraction reasons is ‘+Withdrawn to Publish in Different Journal’ (3 occurrences), when a journal or publisher removes an article from one journal platform to publish it on another. This also indicates duplicate publication by a journal or publisher.

The largest number of retractions involved plagiarism of text (‘+Plagiarism of Text‘ – 38 occurrences), plagiarism of articles (‘+Plagiarism of Article’ – 28) or corresponding euphemisms (‘+Euphemisms for Plagiarism’ – 35). Plagiarism means that the author(s) of an article are not the authors of, at least, one passage of the text, i.e., it is derived from a text by another author but not appropriately cited. The subject of the plagiarism may be one passage of text or an entire article. The category ‘+Euphemisms for Plagiarism’ means information without an explicit statement that the authors used someone else’s ideas, texts or images without proper citation. The three categories appeared 101 times in the surveyed collection.

However, the situation is not always clear. Doubts about referencing or attribution (‘+Concerns/Issues about Referencing/Attributions’) occurred 6 times. This refers to any question, controversy or dispute about whether ideas, analyses, texts or data are properly attributed to the author, i.e., whether they are plagiarised. Occasionally, the related term ‘+False Affiliation’ (1 occurrence), which refers to attempts to raise the status of an author or authors by indicating fictitious affiliations with reputable research centres, may appear. In this group of concerns we also included the normatively similar ‘+Concerns/Issues About Authorship’ (1 occurrence) – any question, controversy or dispute about authorship rights, excluding forged authorship.

A charge equally severe as plagiarism is a fraudulent peer review (‘+Fake Peer Review’). This refers to a situation where a review was conducted deliberately contrary to the journal’s guidelines or ethical standards. There were six such occurrences. An example of an action exposing the practices of ‘predatory’ journals was a provocation organised in 2017 by several researchers from Wrocław and Poznań who created a biography and an online account for a fictitious researcher called ‘Anna O. Szust,’ who then became the editor of dozens of peer-reviewed scientific journals, thereby demystifying the effectiveness of the review policy.20 The authors of the provocation formally withdrew the report of the fake editor afterwards. However, given that the titles of the journals and reviewed articles were anonymised, it is difficult to check whether they are in the RWD.

A specific group of claimants (4 occurrences) can be copyright claims (+Copyright Claims), when there is a dispute over the ownership of the publication. A clear category is ‘+Lack of Approval from Author’ (2 occurrences), when permission from the author(s) to publish is lacking. Similar are ‘+Lack of Approval from Company/Institution’, i.e., lack of approval from an organisation or institution (1 occurrence), and analogously ‘+Lack of Approval from Third Party’ (1 occurrence). A similar category is ‘+Objections by Third Party’ (1 occurrence), meaning a complaint by an external person, company or institution or their refusal to agree to actions taken by the journal or publisher.

A related but different issue is the unauthorised use of data. It may give rise to a retraction labelled ‘+Concerns/Issues About Data’ (1 occurrence), i.e., any questions, controversies or disputes about how data was obtained and managed. Particularly relevant in this case is the protection of personal data, which is regulated by national legislation (Act of 10 May 2018 on the Protection of Personal Data21) and the EU (Directive GDPR22). In this sense, Polish and EU law regulate personal data protection in scientific research separately.

The category ‘+Legal Reasons/Legal Threats’ (2 occurrences) is associated with various claims when steps were taken to avoid or facilitate litigation. An investigation by journal editors or publisher (‘+Investigation by Journal/Publisher’) was recorded 31 times. Another similar category of investigation is ‘+Investigation by Company/Institution’ (4 cases), which refers to the assessment of allegations by the institution (affiliation) of one or all of the authors. The editor publishes a related editorial note when there are significant concerns about the integrity of a published article, even when the investigation of the problems has not resulted in a verdict but there are significant indications that the concerns are valid. In this case, the editors express their concerns and the need to treat the findings cautiously. The rationale for the publication of an editorial note is that there is probative – albeit inconclusive – evidence of research misconduct, and there are objections to the published text unexplained by the authors. An editorial note is often published during an ongoing investigation when a final decision has not yet been made. However, because of the periodical nature of the journal, it is appropriate for the editors to warn the readers of their concerns.

A third party can also conduct an investigation, ‘+Investigation by Third Party’ (1 case). In other words, a person, company or institution that is not the author, journal, publisher or ORI assesses the allegations. Public institutions can also conduct infringement investigations: ‘+Misconduct - Official Investigation/Finding’ (1 case).

Another group of notices involves a defect from the publisher or editor (‘+Date of Retraction/Other Unknown’). This refers to a situation where the publication date is missing or has been modified so that it is not representative of the actual date of the notice. A case like that occurs when publishers overwrite the website of the original article with the retraction information. This type of error was recorded 34 times. The original article was removed (‘+Withdrawal’) from access on the journal’s publishing platform 11 times. Moreover, similar category is a situation labelled ‘+Retract and Replace‘, which refers to the permanent change of status of an article to non-publishable when the same journal later republishes it after significant changes. That happened seven times. Another related category is ‘+Notice - Lack of’ (5 times) when a journal or publisher publishes a notice but the article was removed from the publishing platform.

A similar category of intentional violations involving deliberate fabrication of data is the case of manipulation of empirical material in such a way that it fits the formulated research assumptions. This is referred to by the indicator ‘+Falsification/Fabrication of Data’ (1 occurrence). In addition, a related category appears to be ‘+Hoax Paper’ (1 occurrence), meaning the paper is a deliberately and jokingly edited provocation using false data or information with the specific intention of testing the manuscript acceptance policy of a particular journal or publisher. This refers to a 1996 mystification by the American physicist Alan Sokal.23 Sokal published a paper entitled Transgressing the Boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity in the journal Social Text. The paper was intended to be a provocation, as it described a fictional concept of social development using scientific jargon. Sokal’s mystification sparked a heated debate on the subject and methodology of research in the humanities and social sciences. However, in the RWD database we find no retractions referring to the publication of A. Sokal. Instead, it references two provocative articles written as part of a mystification of ‘grievance studies’ by a collective including Peter Boghossian, Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay.24 However, the retractions of these papers are marked as belonging to the subject of social sciences, one as (SOC) Sexual and Marital Studies and both as (SOC) Sociology.

The next category of faults (31 occurrences) for which the author is blamed corresponds to the category ‘+Breach of Policy by Author.’ It refers to violations of practices adopted by the journal, publisher or institution. ‘+Ethical Violations by Author’ (2 occurrences) occurs when an author goes beyond accepted standards of behavior. This is a general statement of some violation without a specific reason. The retraction may also be ‘+Criminal Proceedings’ (1 occurrence), i.e., criminal court actions that may lead to imprisonment or fines resulting from the publication of the original article.

In philosophy, no case of non-disclosure of a significant competing interest has been reported. However, even in philosophy it cannot be ruled out that there are authors with links to companies, associations or institutions seeking to influence beliefs about the results of their research.

Table 2 shows an attempt to systematise the most common reasons for the retraction of philosophy articles concerning the proposed typology.

| Group | Subgroup | Reasons |

| Honest error notices | +Error in Text | |

| +Error in Results and/or Conclusions | ||

| +Error by Journal/Publisher | ||

| +Paper Mill | ||

| +Unreliable Results | ||

| +Concerns/Issues About Results | ||

| +Error in Analyses | ||

| +Error in Methods | ||

| Misconduct notices | Redundant publication | +Duplication of Article |

| +Duplication of Text | ||

| +Euphemisms for Duplication | ||

| +Taken from Dissertation/Thesis | ||

| +Duplicate Publication through Error by Journal/Publisher | ||

| +Withdrawn to Publish in Different Journal | ||

| Plagiarism | +Plagiarism of Text | |

| +Euphemisms for Plagiarism | ||

| +Plagiarism of Article | ||

| +Concerns/Issues About Authorship | ||

| +Concerns/Issues about Referencing/Attributions | ||

| Peer review manipulation | +Fake Peer Review | |

| Reuse of material or data without authorisation | +Concerns/Issues About Data | |

| Copyright infringement | +Copyright Claims | |

| +Lack of Approval from Company/Institution | ||

| +Lack of Approval from Third Party | ||

| +Lack of Approval from Author | ||

| +Objections by Third Party | ||

| Other legal issue | +Investigation by Third Party | |

| +Misconduct - Official Investigation/Finding | ||

| +Investigation by Journal/Publisher | ||

| +Withdrawal | ||

| +Retract and Replace | ||

| +Investigation by Company/Institution | ||

| +Legal Reasons/Legal Threats | ||

| +Notice - Lack of | ||

| +Date of Retraction/Other Unknown | ||

| +False Affiliation | ||

| +Falsification/Fabrication of Data | ||

| +Hoax Paper | ||

| Unethical research | +Ethical Violations by Author | |

| +Criminal Proceedings | ||

| +Breach of Policy by Author | ||

| A failure to disclose a major competing interest | ||

| Ambiguous notices | Notice - No/Limited Information | |

| +Notice - Limited or No Information | ||

| +Notice - Lack of |

As far as philosophy is concerned, allegations of authorial infringements involving plagiarism are, in some (negative) sense, typical allegations. One may be puzzled by the small absolute number of them recorded in the database, even if we include various euphemisms. However, these violations account for 66.7% of all indications for philosophy publications. The same is true of violations by editors or publishers. The consequences of these most severe allegations are claims and investigations.

The reasons for rejecting the ‘+Criminal Proceedings’ type are puzzling. That was exemplified in the criminal trial of a co-author of the article “Retraction of terror management and stereotyping”25 from the journal Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, published by the Society for Personality and Social Psychology. An investigation into the work of author Diederik A. Stapel led to the decision to withdraw. The investigation was conducted by committees set up by Tilburg University, the University of Amsterdam and the University of Groningen under Professors P. Levelt, E. Noort and P.J.D. Drenth.26 Their findings showed that the articles contained fraudulent data (‘+Falsification/Fabrication of Data’) provided by the accused author. The other co-authors did not know about his activities and were not involved in any way in the generation of the fraudulent data. The criminal trial involved an allegation of fraud against the defendant.

Errors in philosophy form an interesting group, even though many texts that contained errors contributing to retraction have been removed from the database. For example, it is difficult to know what errors were made in texts with the clauses ‘+Error in Text’ or ‘+Error in Results and/or Conclusions’, as after being removed they were published, most likely in corrected versions. They also might have been permanently removed from the web. Exceptionally, a withdrawal note can be found for an article entitled The Negative Association between Religiousness and Children’s Altruism across the World,27 which the authors withdrew as a result of realizing that they had used erroneous assumptions. Similarly, an article entitled Beyond moral dilemmas: The role of reasoning in five categories of utilitarian judgment28 was withdrawn. It differs slightly from the error category ‘+Unreliable Results’ found in retractions.29 These exceptions, however, confirm that most texts with errors are removed from circulation, making it difficult to check the real reasons for the withdrawal. For the sake of the integrity of science, this is undoubtedly a move in the right direction, limiting, however, the study of the philosophy of science or the sociology of knowledge.

An error in the method and, at the same time, in the analysis was indicated at the request of the authors in the retraction of the article Beyond moral dilemmas: The role of reasoning in five categories of utilitarian judgement.30 Its authors discovered that some studies were based on a flawed code that did not allow for adequate data randomization. Using the wrong method led to an error. Hence, the results presented in the text were not sufficiently reliable.

The overall conclusion is that there is still a need for better information about retractions and, in particular, the reasons for retraction. This applies not only to philosophy. Although journal practices are improving, there is still much to be done in this area.

Data from the RWD indicating that philosophy publications account for only 0.48% of retracted articles shows the meagre quantitative potential of philosophy in the global knowledge assessment system. This is not surprising given the funding in natural sciences and strict sciences. These disciplines offer a chance to implement and commercialize knowledge by linking research institutes with business entities. In the social sciences and humanities the opportunities for research with practical application are significantly limited. It is a truism that scientific work is inextricably linked to financial considerations. Philosophy, which does not have great opportunities to commercialize knowledge, has severely limited access to the ‘industry’ of high-ranking journals. That adversely affects its presence in global citation databases, the source from which the RWD draws its data.

The data collected in the RWD does not allow firm conclusions to be drawn on retraction in philosophy due to the low number of such submissions. This particular situation, however, makes one wonder about the reasons. Philosophical research can be retracted like any other. Why are there so few of such retractions?

The main reason seems to stem not from the arrogance of philosophers but from the way scientific output is published. In philosophy – as in other disciplines in the humanities and social sciences – the dominant form of knowledge dissemination is not journal articles but monographs. Contemporary philosophical reflection along with habilitation procedures and requirements for career advancement in universities have shaped a practice whereby the primary form of publication is the book and the article plays only a supplementary role. An article may contain introductory research on a particular problem or develop themes missing from the book, but it is no substitute for an in-depth monographic analysis.

Philosophers are not immune to mistakes and abuses, of course. Sometimes these are only abuses from today’s point of view because at the time of their publication they could not be understood in this way. Such is the case with Der Gegenstand der Erkenntnis31 by Heinrich Rickert, who, instead of starting from scratch, rewrote the text of his opus vitae, added new chapters and even changed his views. During Rickert’s lifetime the book had five different editions, so, in a sense, it can be assumed that each edition is a separate work. Does that mean that Rickert duplicated his scholarly output in an unauthorised way? Not necessarily, as he might have approached the need to change the text differently for COPE. That, however, deserves a separate discussion.

This example is not an isolated one. Indeed, the model of doing science in humanities is different from strict and natural sciences. The latter are most often subject to the withdrawal procedures analysed in this article because their model is cumulative and lets past theses be creatively reworked.

Also worthy of consideration is the hypothesis that publications in philosophy, due to the discipline’s close relationship with ethics, are less prone to scientific unreliability. However, this idealistic understanding of the discipline is very risky, as it postulates no need for retraction and the inherent integrity of scientists today. That again requires a separate discussion.

Data from the Retraction Watch Database is the basis for the analysis presented here. However, it is difficult to describe it as questio facti because the specific qualification of the reasons for rejection is determined by a normative factor (questio iuris). In our case, a COPE norm or another one determines the classification of a specific fact as normed. As a result, the normative dimension permeates the factual one. Problems arise at their interface, as the regulations must be – even if only minimally – general, and the factual situations individual and unique. The ambiguities and inconsistencies in the regulation of retraction show that in this confrontation of rules and exceptions, the exceptions still have the upper hand.

Wager (2010): 40. ↑

COPE (2019). ↑

Resnik, Dinse (2013). ↑

Deculllier, Maisonneuve (2018). ↑

Kozik (2021). ↑

The Center for Scientific Integrity, the parent non-profit organisation of Retraction Watch, made all the data available under a standard data-use agreement. The data are publicly available through a search engine on RWD. ↑

Babbie (2019): 523–525; Frankfort-Nachmias, Nachmias (2001): 104–108. ↑

Hesselmann, Graf, Schmidt et al. (2016): 823. ↑

Marcus (2018). The exception is for records with a tag (PUB), which indicates whether the journal is published by an institution, association or society, but this is not always consistent. ↑

CSI provided the dataset for free for the non-commercial research. Following CSI’s agreement, the shared dataset may not be published, distributed or otherwise made available to third parties. The RWD public search engine presents only 50 results and provides the total number of records matching the search criteria at any moment. At the time of submitting the article for publication (i.e., November 20, 2022), there were already 176 records in the database matching the subject of philosophy. ↑

Andersen, Wray (2019). ↑

COPE (2019): 3. ↑

Andersen, Wray (2021): 5. ↑

Spiroski (2020). ↑

Noonan (2020). ↑

Marcus, Oransky (2018). ↑

COPE (1999). ↑

Zhao (2022). ↑

Puoza, Uba (2022). ↑

Sorokowski, Kulczycki, Sorokowska et al. (2017). ↑

Sejm RP (2018). ↑

GDPR (2016). ↑

Sokal, Bricmont (1998). ↑

Baldwin (2018); Smith (2018). ↑

Renkema, Stapel, Maringer et al. (2013). ↑

Tilburg University (2022). ↑

Worse still, a carelessly prepared procedure may be a reason for questioning the reasons for the rejection of a text. This often results in the creation of various conspiracy theories (e.g. about the alleged toxicity of vaccines (Decety, Cowell, Lee et al. (2015)). ↑

Jaquet, Cova (2021). ↑

Adler (2017); Jaquet, Cova (2021); Fioranelli, Sepehri, Roccia et al. (2019). ↑

Jaquet, Cova (2021). ↑

Rickert (2018). ↑

Acknowledgements: This paper was made possible thanks to the help of a number of friends to whom we are greatly indebted. We are particularly grateful to the members of the German Centre for Higher Education Research and Science Studies (DZHW) and Dr. Felicitas Heßelmann for stimulating comments, valuable guidance and support. We would also like to thank Retraction Watch for collecting the data and, especially, Ivan Oransky for giving us access to the database. We wish to thank Jacek Cachro, Anisja Klinger, Christopher Thornton, and Izabela Zwiech for proofreading and improving the language of the article.

Funding: The research activities co-financed by the funds granted under the Research Excellence Initiative of the University of Silesia in Katowice.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Licence: This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited

Adler J. (2017), Retracted: “The Open Mind: A Phenomenology,” Open Journal of Philosophy 7 (2): 126–167.

Andersen L.E., Wray K.B. (2019), “Detecting Errors that Result in Retractions,” Social Studies of Science 49 (6): 942–954.

Andersen L.E., Wray K.B. (2021), “Rethinking the Value of Author Contribution Statements in Light of How Research Teams Respond to Retractions,” Episteme: 1–16, doi: 10.1017/epi.2021.25.

Babbie E.R. (2019), Badania społeczne w praktyce, trans. W. Betkiewicz, M. Bucholc, P. Gadomski et al., PWN, Warszawa.

Baldwin R. (2018), Retracted: “An Ethnography of Breastaurant Masculinity: Themes of Objectification, Sexual Conquest, Male Control, and Masculine Toughness in a Sexually Objectifying Restaurant,” Sex Roles 79 (11): 762.

Bu Y., Zhao D. (2020), Retracted: “Luteolin Retards CXCL12-Induced Jurkat Cells Migration by Disrupting Transcription of CXCR4,” Experimental and Molecular Pathology 113: 104370.

COPE (1999), “Guidelines on Good Publication Practice,” URL = https://publicationethics.org/files/u7141/1999pdf13.pdf [Accessed 3.03.2022].

COPE (2019), “Retraction Guidelines,” URL = https://publicationethics.org/files/retraction-guidelines-cope.pdf [Accessed 3.03.2022].

Decety J., Cowell J.M., Lee K., Mahasneh R., Malcolm-Smith S., Selcuk B., Zhou X. (2015), Retracted: “The Negative Association between Religiousness and Children’s Altruism across the World,” Current Biology 25 (22): 2951–2955.

Deculllier E., Maisonneuve H. (2018), “Correcting the Literature: Improvement Trends Seen in Contents of Retraction Notices,” BMC Research Notes 11 (1): 490.

Dong Y., Yan X., Yang X., Yu C., Deng Y., Song X., Zhang L. (2020), Retracted: “Notoginsenoside R1 Suppresses miR-301a via NF-κB Pathway in Lipopolysaccharide-Treated ATDC5 Cells,” Experimental and Molecular Pathology 112: 104355.

Fioranelli M., Sepehri A., Roccia M.G., Rossi Ch., Lotti J., Barygina V., Vojvodic P., Vojvodic A., Vlaskovic-Jovicevic T., Vojvodic J. et al. (2019), Retracted: “A Mathematical Model for the Signal of Death and Emergence of Mind Out of Brain in Izhikevich Neuron Model,” Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences 7 (18): 3121–3126.

Fioranelli M., Sepehri A., Roccia M.G., Rossi Ch., Lotti J., Vojvodic P., Barygina V., Vojvodic A., Vlaskovic-Jovicevic T., Peric-Hajzler Z. et al. (2019), “DNA Waves and Their Applications in Biology,” Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences 7 (18): 3096–3100.

Frankfort-Nachmias Ch., Nachmias D. (2001), Metody badawcze w naukach społecznych, trans. E. Hornowska, Zysk i S-ka, Poznan.

GDPR (2016), Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation).Hesselmann F., Graf V., Schmidt M., Reinhart M. (2016), “The Visibility of Scientific Misconduct: A Review of the Literature on Retracted Journal Articles,” Current Sociology 65 (6): 814–845.

Jaquet F., Cova F. (2021), Retraction Notice to “Beyond Moral Dilemmas: The Role of Reasoning in Five Categories of Utilitarian Judgment’,” Cognition 209 (2021) 104572, Cognition 216 (2021): 104860.

Kozik E. (2021), „Jak troszczyć się o życie? Antyszczepionkowe narracje spiskowe w czasie pandemii COVID-19,” Studia Etnologiczne i Antropologiczne 21 (1): 1–19.

Marcus A., Oransky I. (2018), “Retraction Watch Database User Guide. Appendix B: Reasons. Retraction Watch,” URL = https://retractionwatch.com/retraction-watch-database-user-guide/retraction-watch-database-user-guide-appendix-b-reasons/ [Accessed 27.06.2022].

Noonan J. (2020), Withdrawal: “Administrative Duplicate Publication: Thought-Time, Money-Time and the Conditions of Free Academic Labour,” Time & Society 29 (4): 1150.

Oransky I. (2012), “The First-Ever English Language Retraction (1756)?,” Retraction Watch, URL = https://retractionwatch.com/2012/02/27/the-first-ever-english-language-retraction-1756/ [Accessed 24.05.2022].

Puoza J.C., Uba F. (2022), “Statement of Retraction: Modelling and Simulation of Surfacing Welding Remanufacturing for Tunnel Boring Machine Disc Cutter,” Welding International 36 (2): 128.

Renkema L.J., Stapel D.A., Maringer M., Yperen N.W. (2013), “Retraction of Terror Management and Stereotyping,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 39 (2): 264.

Resnik D.B., Dinse G.E. (2013), “Scientific Retractions and Corrections Related to Misconduct Findings,” Journal of Medical Ethics 39 (1): 46–50.

Rickert H. (2018), Der Gegenstand der Erkenntnis. Historisch-kritische Ausgabe, R.A. Bast (ed.), [in:] Heinrich Rickert Sämtliche Werke, De Gruyter, Berlin-Boston.

RWD, Retraction Watch Database, URL = http://retractiondatabase.org/ [Accessed September 22, 2022].

Sejm RP (2018), Ustawa z dnia 10 maja 2018 r. o ochronie danych osobowych, Dz.U. 2018, poz. 1000.

Smith M. (2018), Retracted Article: “Going in Through the Back Door: Challenging Straight Male Homohysteria, Transhysteria, and Transphobia Through Receptive Penetrative Sex Toy Use,” Sexuality & Culture 22 (4): 1542.

Sokal A.D., Bricmont J. (1998), Fashionable Nonsense. Postmodern intellectuals’ Abuse of Science, Picador , New York.

Sorokowski P., Kulczycki E., Sorokowska A., Pisanski K. (2017), „Predatory Journals Recruit Fake Editor,” Nature 543 (7646): 481–483.

Spiroski M. (2020), Retraction: “Five Papers from Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences, vol. 7, no. 18 (2019): Sept. 30 (Global Dermatology),” Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences 8 (B): 573.

Tilburg University (2022), Commissie Levelt, URL = https://www.tilburguniversity.edu/nl/over/gedrag-integriteit/commissie-levelt [Accessed 29.06.2022].

Wager E. (2010), Getting Research Published: An A to Z of Publication Strategy, Radcliffe Publishing.

Zhao X. (2022), Retraction Note: “A Discourse Analysis of Quotidian Expressions of Nationalism during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Chinese Cyberspace,” Journal of Chinese Political Science 2021, 26 (2): 277–293, „Journal of Chinese Political Science”, 1.