Philosophy, Department for the Study of Culture, University of Southern Denmark

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3093-4448

email: lasseni@sdu.dk

Torbjörn Tännsjö has written a clear and thought-provoking book on healthcare priority setting. He argues that different branches of ethical theory—utilitarianism, egalitarianism, and prioritarianism—are in general agreement on real-world healthcare priorities, and that it is human irrationality that stands in the way of complying with their recommendations. While I am generally sympathetic to the overall project and line of argumentation taken by the book, this paper raises two concerns with Tännsjö’s argument. First, that he is wrong to set aside deontic constraints as irrelevant or as pointing in the same direction as consequentialism. Secondly, that his argument against prioritarianism in favor of utilitarianism is insufficient and under-developed. Given these problems, I conclude that we should welcome Tännsjö’s contribution but with these qualifications in mind.

Keywords: Tännsjö; Healthcare priority setting; Prioritarianism, Utilitarianism, Human dignity.

In his brilliant and sharply written contribution to healthcare ethics, Torbjörn Tännsjö defends a hedonist utilitarian account of healthcare priority setting.[1] Tännsjö vividly discusses and defends utilitarianism in comparison to its ideal-theory competitors in egalitarianism and prioritarianism, and proceeds to reflect on what these theories imply for real-world priority setting, touching upon issues such as mental illness, dementia, and terminal diseases among the elderly. I think Tännsjö’s talent for in-depth and detailed ideal-theory analysis, together with his critical engagement with real-world healthcare issues, are exemplary for applied ethics, and I have considerable praise for many of his arguments. However, in this paper I wish to flag two general concerns with his project.

My first concern is that Tännsjö too easily sets aside deontic constraints as either irrelevant or compatible with consequentialist principles for healthcare priority setting. I think many of our ethical intuitions and decisions about what the healthcare system should do (and not do) are grounded upon deontic reasons and rightly so. Or my claim is, less boldly, that Tännsjö has not provided enough argumentation for his claim that we can easily wash these off as they tend to point in the same direction as consequentialist principles. My second concern is with Tännsjö’s (ideal-theory) argument against prioritarianism. Tännsjö claims that a utilitarian +100 calculation of a given scenario could in principle be translated into a negative net result on a prioritarian calculation, due to the asymmetrical prioritarian moral weighting, and that this goes against prioritarianism and in favor of utilitarianism, but I think his argumentation for this claim is inadequate. For these reasons, we should welcome Tännsjö’s contribution but with at least these qualifications.

Tännsjö ends his book with the central conclusion that while utilitarianism, prioritarianism and egalitarianism are broadly similar, and with only minor differences in their real-world recommendations for healthcare priority setting, we are far from seeing their realization in actual health policy. This is best explained, Tännsjö claims, by some form of human irrationality. Tännsjö discusses different accounts of irrationality, but since they have little to do with my argument, I shall set them aside here.

What is important for my critique is the implicit message in Tännsjö’s conclusion that since there seems to be an overlapping consensus between different consequentialist theories, it is surprising (one might think) and at least morally objectionable that real world healthcare priority setting is so far from realizing this principled consensus. For that argument to work, however, two things need to be the case. First, that Tännsjö is right that in so far as these theories are in somewhat (non-ideal) agreement about healthcare priority setting, this agreement is correct. I shall have nothing to say against this. I have issues, however, with some of Tännsjö’s arguments in favor of utilitarianism against competing theories in the first part of the book (one of which I shall elaborate below), but for what it is worth, I find the thesis about the existence of overlapping consensus on healthcare priorities in real life generally plausible. In other words, I agree that distributive principles of different shades would in general recommend quite similar healthcare policies which are significantly different from the priority settings of healthcare systems today.

Moreover, while I believe Tännsjö provides some insightful and thought-provoking examples of this, there is a second necessary part to this argument. For Tännsjö’s argument to hold, it must also be the case that utilitarianism, egalitarianism, and prioritarianism (or leximin priority) together exhaust our ethical considerations relevant for healthcare priority setting, or alternatively that relevant moral considerations not covered by these consequentialist theories point towards the same implications for priority setting. I find that highly doubtful, and Tännsjö nowhere provides a successful argument for this.

This point then raises the following question: what are the alternative relevant ethical considerations? While I am in no position to give a definitive account of this, one is baffled by the lack of emphasis in Tännsjö’s analysis on deontic constraints. Tännsjö restricts his analysis to consequentialist considerations and rarely even mentions deontology, which is surprising since deontic considerations—e.g., patient autonomy, bodily rights, fairness and the distinction between killing and letting die—are typically thought to hold significant relevance for specific healthcare priority-setting decisions, and they often seem to move our judgement against consequentialist considerations.

Empirical studies report that the public is often sensitive to the conflict between deontic and consequentialist considerations. In a survey experiment, Peter Ubel and his colleagues presented subjects with two different colon cancer screening programs and asked them to recommend one over the other. The first program was less effective but cheaper, so that everyone could be given a chance, but fewer cancers (1000) would be detected and treated. The second was expensive but twice as effective—i.e., half as many people could be screened but more cancers (1,100) would be found and treated. Ubel et al. found that when the cheap but less effective test was offered to everyone, subjects’ recommendations revealed a small majority (56%) in favor of the less effective test, despite this implying 100 more cancers not treated. Thus, the study concluded that what might be called a deontic consideration of fairness (in the sense of giving people an equal chance) is a strong moral concern for the subjects.[2]

This is not to deny the importance of consequentialist considerations. These are indeed important in healthcare priority setting. But if Tännsjö’s argument is to succeed, and thus we have strong reasons to adjust healthcare systems to comply with the consequentialist consensus, this must imply that deontic considerations are either not important or simply point in the same direction as their consequentialist counterparts. As far as I can see, this implication is false, and Tännsjö has not provided sufficient arguments to the contrary. In the preface of the book, Tännsjö explicitly set aside deontic considerations with reference to the somewhat optimistic assumption that there will be no conflict between them and consequentialist resource allocation. “I set these problems to one side in this book by assuming (with a few exceptional passages where I touch upon the question of euthanasia) that the allocation of scarce resources can be performed without any violation of any putative deontological constraints.”[3]

In a later passage, Tännsjö discusses euthanasia and here leaves open the question of whether there could be deontic constraints on assisted death. His conclusion is thus cleverly disjunctive in saying that, “if euthanasia is immoral in these circumstances, then morality comes with a high burden to be carried by the patients.”[4] Thus, Tännsjö is not unaware of the importance of deontic constraints at times, but neither does he give them the attention many would say they deserve. There are many reasonable deontic constraints on what a healthcare system can and should do with important implications for priority setting, which do not necessarily fit consequentialist reasoning, but which nevertheless seem to be not easily written off.

It is not my purpose here to give a full account of deontic constraints—and I have no personal favorites. My point is very general, namely that Tännsjö is too swift to write off deontology as irrelevant for healthcare priority setting. One might even agree with Tännsjö on his consequentialist analysis (as I for example roughly do) and still find it morally reasonable that health systems do not work as a perfect reflection of that. An example is called for, yet instead of giving some standard thought experiment eliciting intuitions about the deontic importance of not killing or harming someone, the protection of personal autonomy, respect, dignity, rights etc., I will employ Tännsjö’s own example. This is not because I think there is anything wrong with hypothetical examples (I will use some myself below), but because turning to Tännsjö’s own case better illustrates how I think he is neglecting deontic constraints in some cases where they seem to hold relevance.

In the first part of chapter eleven, Tännsjö takes the ethical platform of the Swedish National Priority Commission as his example. The Commission suggests three principles, the first of which is about human dignity.

Now, there is clearly a basis for a critical discussion of this ethical platform on several issues but it is not my aim to defend it as it stands. In fact, while I am quite sympathetic to much of what Tännsjö has to say about it, I believe it is a good illustration of how Tännsjö thinks too little of the importance of deontic moral considerations for real world healthcare priority setting. I think it is fair to interpret the first two principles as mainly raising deontic constraints on what we will accept our healthcare system doing. There are priority decisions that we will simply not stand for, regardless of how good their comparative aggregated consequences are. This is, at least, the central message of the first principle. We will not accept, the principle says, that anyone be treated with less than the dignity we expect to count for all human beings. And while this is certainly underspecified in terms of what will be considered acceptable and what will not, there are indeed several important priority-setting implications of having such a principle. We shall not accept, we could imagine, any type of neglect of care, or that people in the last stages of life be left to a less than a dignified ending, or that people with severe conditions for which we can in fact provide effective treatment be left with no access to such treatment.

Here is Tännsjö’s reading of the principle of human dignity.

The first (rather pompous) principle gives little advice about how to ration medical resources among human beings (I suppose it indicates that human interests take precedence over the medical interest of other animals; there is room for veterinary medicine only after all human needs have been met). It does rule out, however, some kinds of obviously illegitimate grounds for priority setting. It is, for example, said that (moral) desert cannot ever be a ground for different medical treatment, nor can gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and so forth.[6]

This seems a very crude and naively utilitarian reading of principle of human dignity for medical prioritization, taking as the central part that human interests take precedence over the interests of other animals. While this indeed seems to be a principled implication of the first principle as it stands, I doubt that this is thought to play any role in real life priority setting. In any case, one would not expect an ethical platform for real world healthcare policy to take on comparisons between human and non-human animals.

More importantly, when looking solely at humans, I think much more could be said in defense of the first principle. It seems to me to latch on to the idea of human dignity as interpreted in the Kantian tradition. According to Kant, human dignity refers to the “inner worth” of humans “raised above all price”, and this fundamental worth related to personhood of humans demands respect in the sense of not violating the rights of that person to form and pursue personal life projects.[7] Dignity, according to Kantians, is a status worthy of respect based on the absolute worth of the person bearing it.[8] One further elaboration of the Kantian form of dignity is for example that of Lennart Nordenfelt in his account of menschenwürde.[9] That is, the special account of dignity anchored in the personhood of being human. For Nordenfeldt, menschenwürde is different from other applications of the idea of dignity as referring to merit, agency or identity, firstly because it is universal, it applies to all humans, and second, because it is inalienable in that no one can lose their dignity in this sense (not even by death). Human dignity in this Kantian sense implies that all humans are owed respect qua being human persons and that this implies that there are certain ways we will not allow that they be treated.

What this implies for healthcare priority setting is not merely that human interests take precedence over animals, but that there are some entitlements that cannot under any circumstances be taken away from individuals. How does this matter? Well, one can think of many instances where this ideal would find relevance for healthcare priorities and where it would definitely run counter to consequentialism. For instance, imagine the following case. Suppose we can find healthcare resources to treat a group of young patients for a non-fatal but relevantly harmful disease, but only by taking resources currently used to maintain minimal care for elderly and patients suffering from severe dementia. Now, it is important to stress that pleasures (or hedons, as Tännsjö uses the term) are also valuable for dementia patients, but since their dementia to some extent compromises their awareness and experience of their own condition, and since they have fewer life years left in any case, we can easily imagine that it could be justified on consequentialist grounds to redistribute the resources for the benefit of the group of younger patients.[10] However, many would find this a violation of our deontic duty to respect human dignity. Call this the case of neglect against the needy.

To take another case, imagine that we can decide whether or not to reallocate healthcare resources from one group of patients (A) to another group of patients (B). The two groups differ in their type of condition. A’s are suffering from a rare disease for which we have only one available form of treatment which is comparatively expensive and inefficient. B’s, on the other hand, are suffering from a common disease for which there are many available treatments, and these are much more efficient. Now, on Tännsjö’s utilitarianism, we can easily imagine that the preferred outcome would be to reallocate resource from patients in group A with the rare disease to patients in group B, since this would result in a total positive outcome of hedons (say it would produce 100,000 extra hedons for B against only a loss of 50,000 hedons for A), despite the fact that group A has no alternative medical treatment for their condition. However, many would find this a violation of our duty to respect the dignity of patients in group A.[11] Call this the case of neglect of patients’ right to available treatment.

Most people would find these cases utterly unethical, but according to Tännsjö’s hedonist utilitarianism they cannot be. I take it that something like this is what grounds the first principle in the ethical platform. Thus, what the first principle indicates (if not its lexical priority) is that human dignity is a moral bedrock ideal placed within deontic consideration. We will not stand for the undignified treatment of anyone, regardless of how much benefit others can gain from this. Perhaps consequentialists are right that the consequences outweigh this ideal, and that we would be wrong to overstate the status of human dignity in healthcare priority setting—and consequently, that the Swedish commission is wrong to hold this as their primary principle. But I think this needs an argument that takes the deontic reasoning seriously and explains why we should dismiss this consideration in this case.

Many would indeed see a principle of human dignity to apply to healthcare priority setting and I have given some examples showing that this is very intuitive. Of course, one might choose to disagree, either because you don’t share my intuition or because you think there are good reasons to dismiss them, but you would need an argument for that and you cannot simply assume that deontic considerations go along the lines of consequentialism. I leave this objection to Tännsjö here, and I turn now to my remark on his rejection of prioritarianism.

According to Tännsjö, prioritarianism is consequentialist in a way parallel to utilitarianism. That is, it is an additively maximizing form of consequentialism, it is just that the maximization must be weighted by a function giving priority to the worse off.[12] Prioritarianism in its generic form says that it matters more to benefit people they worse off they are.[13] To make it clearer how prioritarianism is distinct from egalitarianism and utilitarianism, we can note two important elements. First, the benefits given to worse-off people have more intrinsic moral weight than benefits to better-off people. This makes prioritarian weighting distinct from utilitarianism, which gives merely indirect priority to the worst off for reasons related to decreasing marginal utility. Thus, prioritarians believe, we have reasons to favor redistribution to the worst off even when this is not utility-efficient. Moreover, contrary to egalitarianism, prioritarians’ concern for the worse-off refers to their absolute rather than their comparative level of wellbeing. Prioritarians differ on a distinction between lifetime and time-slice views.[14] Time-slice prioritarians are concerned with evaluations at particular instances or periods. Lifetime prioritarians, on the other hand, are concerned with distributions over complete lives. This implies that lifetime prioritarianism might give priority to one person over another, despite the second person being worst off now, if the first person has been worse off than B in the previous parts of their life.

As mentioned, Tännsjö’s general argument concerning real-world priority setting relies on overlapping consensus between utilitarianism and prioritarianism. However, when it comes to the ideal-theory philosophy. Tännsjö presents an argument against the prioritarian weighting. His argument is this.

Think of a person whose life is threatened by a disease. If he is not treated, then he will die immediately. If he is treated, then he will live one additional year. However, there will be ups and downs during this last year. In order to stay alive, he will now and then have to go through short sessions with painful therapies. Assume that, when we sum the happiness in his remaining year, the net will be +100. However, when we add the weights given by prioritarianism, because of the extra weights given to his downs, the moral value of his additional year will be -1.[15]

Since the net negative value of suffering is larger according to prioritarianism than the net positive value of pleasure, Tännsjö believes that his imagined case poses a possible problem for prioritarianism, because it shows that a life that is clearly worth saving (at least according to utilitarianism) turns out not worth living, and thus not worth saving, on a prioritarian calculation. I think there is a need to explore and clarify how utilitarians and prioritarians disagree on this issue.

To exemplify, Tännsjö’s case can be unfolded like this.[16]

Table 1. Tännsjö’s case exemplified

| Additional Year | Utilitarianism | Prioritarianism |

|---|---|---|

| Quarter 1 Intense pain | -200 | -245 |

| Quarter 2 Moderate pleasure | +100 | +92 |

| Quarter 3 Moderate pain | -100 | -120 |

| Quarter 4 Intense pleasure | +300 | +272 |

| Total Year | +100 | -1 |

Table 1 illustrates a charitable exemplification of how Tännsjö interprets the difference between utilitarian and prioritarian accounting of the case. As illustrated, each quarter with a negative value will have a higher negative value for prioritarianism than for utilitarianism, and each quarter with a positive value will have a reduced value according to prioritarianism.

Tännsjö anticipates a response to his criticism provided by Shlomi Segall, who argues against his case that “on a prioritarian calculus, ups and downs simply cancel out each other.”[17] But Tännsjö cannot make sense of this and thinks it must be wrong. “This is what they do according to utilitarianism”, he concedes. “One day at minus ten is cancelled out, according to utilitarians, by another day at plus ten. However, if the prioritarian concurs in this judgement she has allowed her theory to collapse into utilitarianism.”[18] In my view, there is some truth to both sides of this dispute, and it seems to me that Tännsjö and Segall misunderstand one another. Perhaps the misunderstanding is mostly on Segall’s part, since you might say that he is misreading Tännsjö’s objection, which can hardly be Tännsjö’s fault. However, there seems to be an important point in trying to clarify what is going on to elaborate the dispute further.

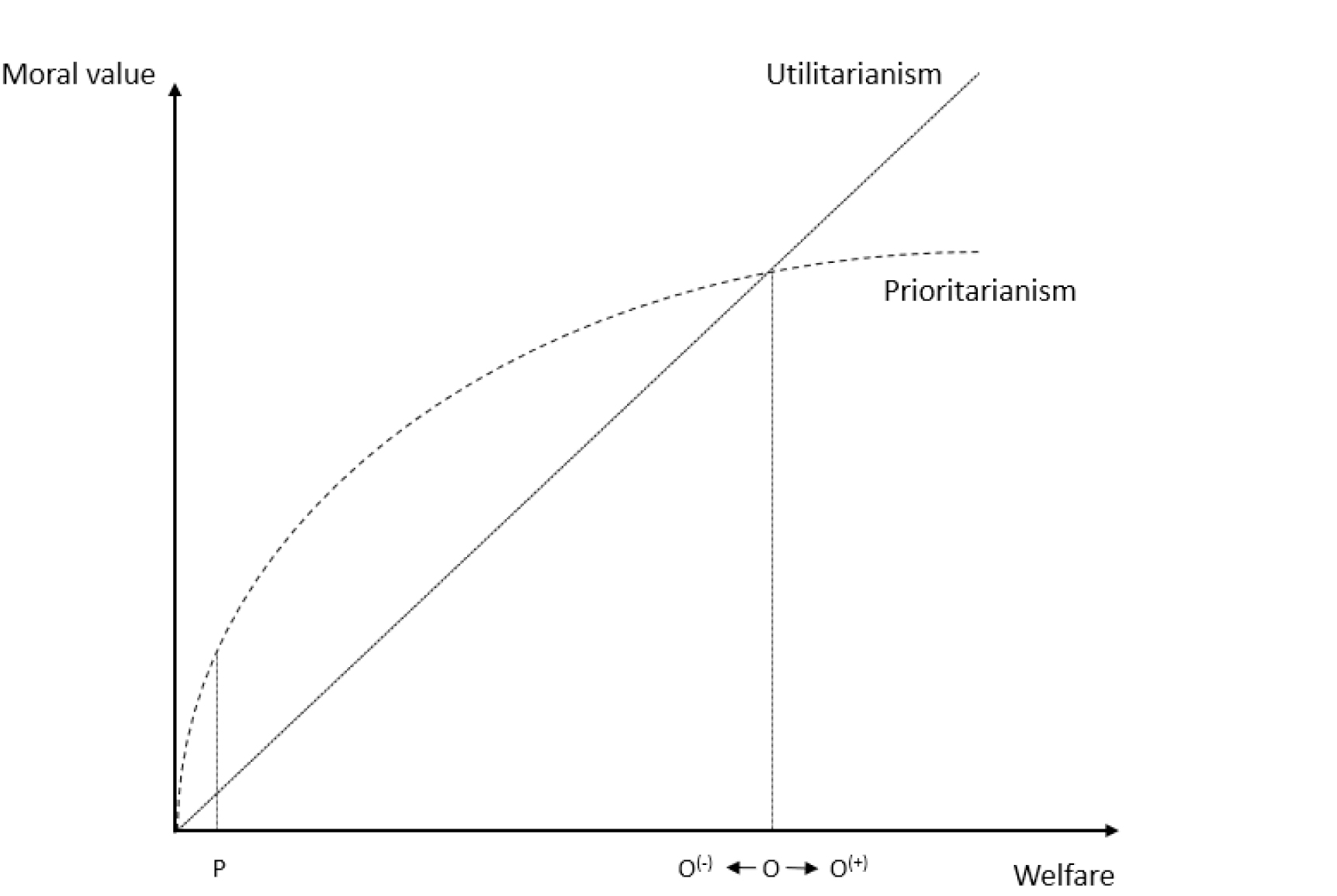

Figure 1. Utilitarianism and prioritarianism

One way to give more substance to Segall’s response is the following: Tännsjö’s interpretation cannot be accurate, since it must be the case that pleasures and pains are evaluated from the same constant point on the prioritarian and utilitarian curve for this to be true. That is, where Quarter 1’s intense pain is measured from point O to point O(-) in figure 1, Quarter 2’s moderate pleasure is measured from point O to point O(+). If this is the case, then pleasures and pains of equivalent moral value according to utilitarians could result in a net negative value for prioritarians due to the discounting value of pleasures. Yet, Segall’s response could say that this is not the right way to interpret the case. The pleasure in Quarter 2 must be measured from O(-) since the person in question is now worse off than before and thus its moral value must proceed upwards along the same slope as the pain in Quarter 1 went down. When this is the case, the moral value of added welfare upon the loss of a similar amount of welfare must also cancel out the previous negative moral value for prioritarians. By this interpretation, the important point is not the fact that prioritarians give more weight to suffering than utilitarians while discounting the value of the benefits, but rather that the moral value of benefits in both views must go up along the same curve as suffering went down. If this is the case, ups and downs do in fact cancel each other out.

To make this more relevant, consider the following example. Imagine a situation which seems like a zero-sum case (assumed on utilitarian grounds). For example, imagine that a fully functioning patient suddenly suffered from paraplegia, but that we shortly thereafter discover a completely safe pill to rectify this handicap. The patient is provided with the pill and recovers full health. Of course, we can speculate that there are some associated opportunity costs, in that the patient has been unable to pursue some of his preferences while being paraplegic, but let us assume that by taking the pill he is brought back to the same level of welfare—e.g., we can imagine that his pleasure in playing golf after his treatment was equivalently above average to make up for missing a day on the golf course during his illness. If we are pleased with that assumption, we could interpret this case as an example which is similar to what Tännsjö has in mind when he writes, “One day at minus ten is cancelled out, according to utilitarians, by another day at plus ten.”

Now, if Tännsjö is correct in his assessment of prioritarianism, and we accept the interpretation of the case I have ascribed to Segall, this must imply that taking the pill for prioritarians will have less moral value than what can make up for the negative value of him experiencing paraplegia, but this is obviously not the case. Intuitively, they must have the same value, and this must be the case across different additive distributive theories. Prioritarianism does not have that implication nor do prioritarians believe it does. That it matters more to help people the worse off they are does not imply that rectifying suffering holds any less value than the reciprocal negative value of that exact suffering. We can again see this in Figure 1 by looking at the prioritarian curve. On the assumption (which is accepted here) that rectifying the suffering by taking the effective pill against paraplegia has the same welfare gain—and thus the same prudential value for the patient in question, the moral value represented by moving back up must be the same as the lost value of dropping down.

However, I am confident that this is not what Tännsjö has in mind and thus I suspect Segall could be misreading him here. Let me elaborate upon this point with another example. Tännsjö believes that suffering has more net negative value according to prioritarianism than according to utilitarianism. Yet he is explicitly ready to admit that the prioritarian value of preventing a harm is equivalent to the value of rectifying that harm. “I agree,” he writes, “that it is equally valuable to raise someone from ninety to one hundred, say, as it is to prevent her dropping from one hundred to ninety, provided she is staying at this level for the same time. However, I do not see any relevant point made in this observation.”[19] This is a bad fit for the interpretation of Tännsjö’s case which I have ascribed to Segall (of course, I could be wrong about the above being Segall’s interpretation, I am merely trying to make good sense of his response). But this, I conjecture, is simply because the above interpretation is a misreading of the problem Tännsjö intended to pose. On his interpretation of prioritarianism, the ups and downs do not cancel each other out, because any “down” (and back up) involves some time spent in suffering, and any “up” (and back down) involves some period of pleasure. In other words, the point of measuring pleasures and pain in this interpretation should indeed be held constant since the counting of negative value continues as long as the person is below the initial point of departure from which the counting of moral value begins.

To see this, let us revisit the paraplegia case above. Imagine that the one day spent in paraplegia amounts to some amount of pain (-100). After taking the pill, the person is back to the initial functioning level. On Segall’s interpretation, this relief of the pain amounts to a similar amount of positive value (+100), but this is not so for Tännsjö, because the -100 represents the loss of welfare during the time spent in pain. In other words, the pill represents the end of the period in which we count suffering. On this interpretation, the negative moral value (-100) is represented not in moving from O to point O(-) but in moving there and back again, and thus in order to cancel this out, we would have to have an equivalent move upwards (and back again) from point O. However, as is evident, this moving up from O to point O(+) and back would not cancel out the negative value of the previous move down on prioritarian grounds (from O to point O(-) and back to O) because of the discounted moral value of benefit at this point. On this interpretation, which I think is a fair description of Tännsjö’s view, it would be possible, as he claims, that prioritarians would find life not worth living, despite the fact that we have utilitarian grounds for the opposite.

Now, the central question is whether this gives sufficient grounds for rejecting prioritarianism. Admittedly, Tännsjö does not think so himself, but he believes his case poses an intuitive case against prioritarianism in comparison with utilitarianism.[20] However, I find this highly speculative. It seems to me that our intuitions on what some amount of pain and some amount of pleasure is worth in comparison to death is not so easily accounted for, and I suspect that our intuitions about the particular case in question turn on which view has been primed as the default accounting theory. Tännsjö’s intuitive objection rests on the assumption that it is indeed a life worth living (which it is only on utilitarian grounds), and thus that prioritarianism is in fact wrong in its assessment.[21] However, even if we granted Tännsjö’s interpretation, this need not be the case, and he has not provided sufficient argumentation for why we should accept a utilitarian calculation before a prioritarian one. Perhaps one explanation for why we should favor the straightforward utilitarian calculation is that we should be skeptical towards accounts that would find lives not worth living (i.e., prioritarianism) when there are other accounts on which the same lives are deemed worthwhile. Perhaps it runs against prioritarianism that it seems harsh in this particular instantiation.

Yet while this can possibly explain away part of our intuitive reaction, it cannot count as a reason against prioritarianism. If this was the case, we would have similar intuitive reasons to reject utilitarianism, if we could find cases where prioritarianism seemed a more intuitive default. Imagine the following case. A patient will die immediately if she is not offered care, but with care she can live for an additional year. The condition of the patient now without treatment is such that her life is barely worth living. Since the treatment will involve a significant amount of pain and discomfort, her additional year will turn out to have net negative value. However, we can partially prevent some of this with a newly invented pill. The pill, if given, will prevent the worst drops in life quality but it will not prevent all of the pain.

Due to the prioritarian curve, as Tännsjö observed, suffering will have an increasing negative value as it gets worse, whereas according to utilitarianism the negative value of suffering is constant. Similarly, since it is, as Tännsjö agreed, “equally valuable to raise someone from ninety to one hundred, say, as it is to prevent her dropping from one hundred to ninety”, preventing suffering must, on a prioritarian account, have increasing positive value as suffering gets worse. Consequently, it must follow that it is now possible that offering care to secure one additional year of life for the patient while preventing the worst suffering but not all, her suffering could add up to a total positive moral value according to prioritarianism, while the net result on a utilitarian accounting would be negative. In this case, utilitarianism seems to allow the loss of a life that (in some interpretations) seems worth saving. Does this imply that utilitarianism is wrong? I don’t think so, but it seems to imply that Tännsjö’s case does not necessarily work well in arguing against prioritarianism.

Before I conclude, I wish to make one additional and more simple point. The dispute between Tännsjö and Segall so far has concerned the way prioritarianism discounts moral value as people get better off. So far, nothing has been said about the difference between utilitarianism and prioritarianism in regard to their view on the intrinsic moral worth of benefits at particular absolute levels of welfare. However, since it matters more intrinsically for prioritarians to benefit people the worse off they are, it is arguably the case that benefitting people that are very badly off has higher moral value for prioritarians than it has according to utilitarians. It is important to note that this need not in principle be the case, but the argument for why we should assume so is that because of the discounting moral value of benefits, then if this assumption is false, then benefits will always be worth less for prioritarianism than for utilitarianism. This seems wrong. Hence, we can assume that benefits given to very badly off people are worth more on prioritarian grounds than on utilitarian ones. In Figure 1, for example, this is the case at point P.

If this is the case, it is easy to imagine a patient in a condition that makes her life of below zero value, and that we can benefit this patient with some treatment which will then be worth comparatively more to a prioritarian than a utilitarian. Importantly, note that this does not rescue prioritarianism from Tännsjö’s objection. Even at very low levels of welfare (even below zero), it will be the case that prioritarianism could end up with a net negative moral evaluation of a case which utilitarians find to have net positive moral value, but Tännsjö neglects the fact that at these levels of welfare, the moral value of benefits are generally much higher for prioritarians than for utilitarians. Again, this leaves us with the possibility that a case that can result in positive moral value for prioritarianism turns out to have a net negative value on a utilitarian account. As before, I fail to see that this should be detrimental to utilitarianism, but it renders Tännsjö’s critique of prioritarianism less credible. The general point is that in some rare cases the mere fact that prioritarianism seems to imply a net negative value when utilitarianism does not, might be of very limited importance, since we can easily design situations in which the opposite is the case. Thus, these cases don’t seem to help us much in our deliberations over which theory is the most plausible.

I am generally sympathetic to the project in Tännsjö’s book, and I find many of his arguments and his overall conclusion quite plausible. However, I have raised two concerns in this paper. Firstly, that Tännsjö is too hasty in setting aside deontic constraints as an important moral contributor to real world healthcare priority setting. Second, that Tännsjö’s argument against prioritarian moral weighting does not justify or form the basis for a rejection of prioritarianism and barely poses a credible intuitive problem. Both these concerns point to the need for further elaboration and argumentation.

I owe my thanks to Anna Christine Dorf, Andreas Albertsen, Kasper Lippert-Rasmussen, two anonymous reviewers and the editor of this special edition of Diametros for helping me with the paper. I also thank Torbjörn Tännsjö for writing a brilliant book that made me think about these issues. The research was founded by the Independent Research Fund Denmark, grant number DFF 9037-00007B.